Wine Cellars or Rocket Silos? Lebanon Has a Choice to Make.

A viral tweet proposing to turn Hezbollah’s tunnels into wine cellars forces Lebanon to face a long-avoided question: will it keep digging into conflict or rise to build a state worthy of its people?

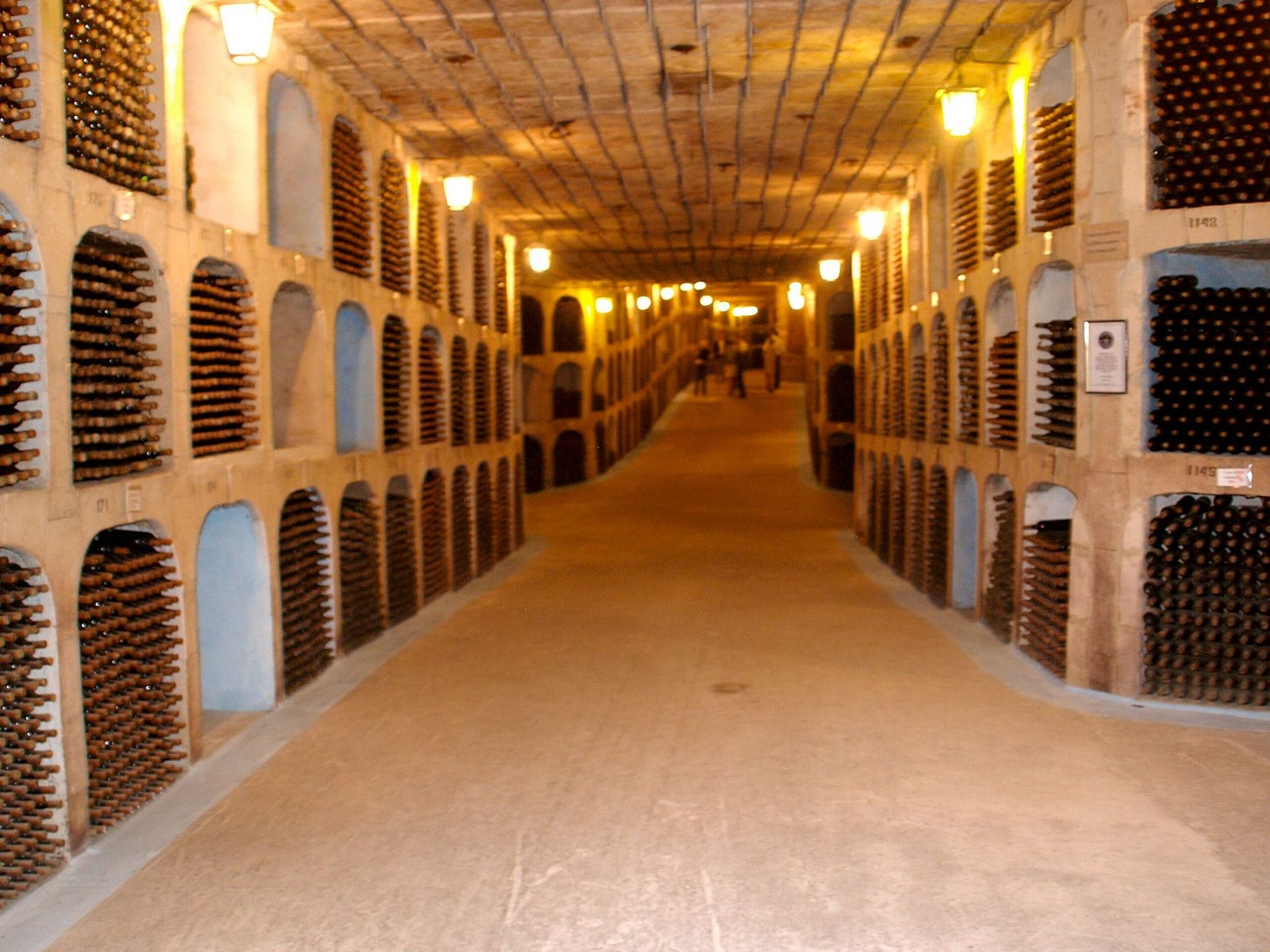

“A cluster of bottles, not bombs... I will formally propose to the Lebanese Army and government not to destroy or demolish the discovered tunnels in the South, given their potential added value. They could be transformed into facilities with economic and touristic significance, specifically, wine aging cellars similar to Milestii Mici in Moldova…”— MP Abdel-Massih, X (formerly Twitter), October 2025

When Lebanese Member of Parliament (MP) Abdel-Massih posted these words, proposing to transform Hezbollah’s tunnels in southern Lebanon into wine-aging cellars, social media reacted with disbelief. Some called it satire. Others thought it was a stroke of genius. The majority wondered if he was entirely serious. But beyond the humor and absurdity, the comment struck a deeper chord: Lebanon has a choice to make. Should it use its underground tunnels to fuel more war and destruction, or to create jobs, tourism, and economic growth?

The MP invoked Milestii Mici, a real complex of tunnels in Moldova that was once used for military storage during World War II. After the war, these tunnels were repurposed into the world’s most extensive wine cellars, housing millions of bottles, many of which are several decades old. It was an audacious transformation.. What was once a secret bunker for storing weapons is now a tourism hub that preserves the country’s invaluable aroma. Abdel-Massih’s idea echoed that story, whether he meant it literally or as a provocation. What if Lebanon’s tunnels, dug for war, could one day become vaults of prosperity?

Of course, anyone who knows southern Lebanon understands the implausibility of such a plan. The region’s social and religious fabric, bar a few Christian towns and villages that never had such tunnels to begin with, would never permit wine production, let alone turn former military tunnels into tourist attractions. The proposal clashes with cultural reality. Yet it is precisely this clash that gives the idea its force: it exposes how far Lebanon has drifted from a shared sense of what progress even means.

A wine cellar beneath Bint Jbeil or Aita al-Shaab is unthinkable, but so too is the notion that Lebanon should keep living beneath the surface (literally and figuratively) to sustain a permanent state of war. The MP’s words may have been sardonic, but they captured a nation’s exhaustion with destruction and its yearning for reinvention.

Lebanon’s soil has always contained contradictions. In the Bekaa Valley, vines trace their ancestry back 7,000 years to Phoenician traders who shipped jars of wine across the Mediterranean. That same valley later hosted militia camps and rocket launchers. The country has long balanced two instincts: to cultivate and to conceal.

Wine represents patience, skill, and commerce—its progress measured in years and vintages. Weapons represent secrecy, fear, and death—measured in milliseconds and detonations. In one, the Lebanese legacy of terror breathes and matures; in the other, it suffocates.

Lebanon’s existing vineyards, from Ksara to Kefraya, have survived wars and blockades. Although these vineyards export modestly, they embody a crucial idea that prosperity can be grown, but it can never be imposed. Meanwhile, the economy of arms and smuggling has enriched no one, isolated the country, and reduced its people to pawns in other nations’ wars. One tunnel hosts barrels that age with grace, the other hides rockets that never age well. The first invites sommeliers; the second invites sanctions, airstrikes, and invasions.

The metaphor of bottles versus bombs reflects two real scenarios now confronting Lebanon. The first is the familiar one: perpetual war—a state sustained by the logic (or lack thereof) of the resistance delusion, with infrastructure built for concealment, young men trained for an endless conflict they did not start, and families torn apart in schools and basements because they have no home to return to. This path breeds dependency, fear, and decay.

The second scenario imagines creative survival: it’s about turning ingenuity toward rebuilding rather than hiding, toward culture and tourism, toward industries that could bring employment, dignity, and global connection. It does not deny Lebanon’s security concerns; it simply argues that no society can live forever in a tunnel.

The irony of Abdel-Massih’s tweet is that, in Lebanon, imagination has become a political stance. To propose a wine cellar, even hypothetically, is to propose light in a place that has known only darkness.

Moldova’s Milestii Mici overhauled a symbol of conflict into an engine of prosperity. It now employs hundreds, attracts tens of thousands of visitors from around the world, and exports its reputation alongside its bottles. Lebanon, by contrast, keeps digging, not to mine for potential, but to bury it.

The country’s economic collapse has already destroyed the livelihoods of its farmers, vintners, hoteliers, and traders. Everyone’s lives were devastated. Every year, thousands of skilled young Lebanese emigrate. The ones who stay are left between the ruins of an economy and the delusional rhetoric of endless fighting. The nation that once prided itself on being a crossroads of culture now lives under a self-imposed siege.

Abdel-Massih’s imagery of bottles, not bombs, confronts this contradiction directly. Lebanon has the talent, the climate, and the heritage to export beauty. Yet it chooses to import fear and export the youth.

Still, it would be naïve to ignore Lebanon’s cultural boundaries. Southern Lebanon’s predominantly Shiite communities would never sanction vineyards or wine tourism. For many, wine remains a symbol of Western indulgence, incompatible with religious norms. But the point is not fermentation; it’s transformation.

The debate reveals a more profound truth: Lebanon’s divisions are not just political or sectarian, but philosophical. What constitutes progress? For one part of the country, it is resistance and self-preservation; for another, it is openness and enterprise. This clash of visions has paralyzed the nation for decades and will continue to do so for many more, unless drastic change happens.

The South may never age wine, but Lebanon as a whole must decide whether it will age at all: Will it mature, or will it remain trapped in perpetual adolescence, forever justifying its own destruction?

Perhaps the MP’s post on X was a challenge to Lebanon’s imagination, a plea to see possibility where there is only rubble. What if the country could turn its ingenuity away from rocket-hiding tunnels and toward the kind of craftsmanship that makes the world pause, taste, and remember?

Maybe one day, visitors will descend into the cool limestone beneath the South, not to inspect missile caches, but to sip a Shiraz that carries the scent of renewal. Maybe the tunnels themselves will remain closed, but the idea they evoke will survive: to repurpose pain into prosperity.

Until then, Abdel-Massih’s message will remain both satire and prophecy, and a reminder that Lebanon’s future depends on what it chooses to cultivate beneath its soil: bottles or bombs, trade or terror, maturity or decay.

In the meantime, the vineyards are waiting. The tunnels are, too.

Middle East Uncovered is powered by Ideas Beyond Borders. The views expressed in Middle East Uncovered are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Ideas Beyond Borders.

I truly hope Lebanon can build a thriving wine industry one day. But the sad reality is that Israel will never let Lebanon live in peace until Hezbollah and the Lebanese army learn to work together to defend their country and its air space. Defeat the Zionists who keep attacking you, then you can grow all the wine you want.

https://mirrorsfortheprince.com/how-muslims-should-react-to-americas-inevitable-withdrawal/

The Zionists have been so damaging to the entire world, and especially to the Middle East. Southern Lebanon is of course under "Greater Israel" expansionist threat, from the occupation currently within the rough borders known as Israel.

What did twitter-x have to say about that?