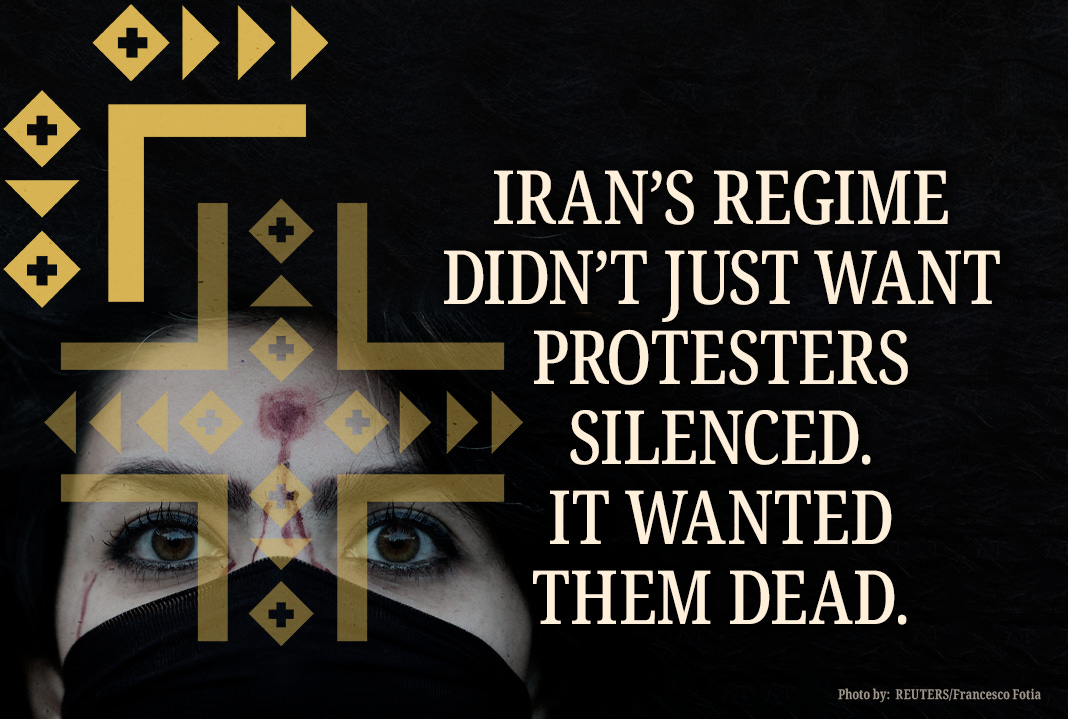

Iran’s Regime Didn’t Just Want Protesters Silenced. It Wanted Them Dead.

A protest survivor recounts how January’s demonstrations became a manhunt, with security forces firing live ammunition at unarmed civilians—and urges the world not to abandon the Iranian people.

Middle East Uncovered uses pseudonyms to protect our sources in Iran.

The first thing Kazem told me was that no one believed the regime would use live ammunition against unarmed civilians.

“We thought it would be tear gas,” he said. “Maybe rubber bullets. That’s what everyone prepared for.”

Kazem had never protested before January 8. He and his wife were not activists nor part of an organized movement. Like many middle-class Iranians, they were getting by materially, working, planning home renovations, living within the narrow space the Islamic Republic allows people who keep their heads down.

That changed after the Twelve-Day War in mid-2025, when Israel struck Iranian targets, and the regime claimed victory despite visible military humiliation. Something shifted in the country afterward—people were beginning to see cracks in the regime’s facade. It felt like a window of opportunity to fight for something better might be opening. To Kazem and to many others, the Islamic Republic emerged from those twelve days exposed and diminished.

“After June 2025, many women stopped wearing their hijab,” Kazem told me. “Many women stopped covering their hair at all… including my wife.” One reason, he said, was technical. “Their surveillance cameras stopped working.” Another was psychological. “They lost a lot of power. They didn’t feel as scary anymore.”

When Reza Pahlavi, the exiled crown prince, called on Iranians to march on January 8 and 9 (the Iranian weekend), Kazem heard something different from past appeals. This time, people around him were actively preparing to make their voices heard.

“Everyone was talking about it,” he said. “Neighbors. Family. Friends. People were saying, If we don’t go out this time, then we shouldn’t complain anymore.”

So they prepared for what they believed the regime would do. During the Woman, Life, Freedom uprising, the regime notoriously fired rubber bullets at protestors, often injuring or blinding those who were hit. That was the level of force Kazem and his wife were expecting.

So they bought workshop goggles to protect their eyes, layered their clothes to blunt the impact of pellet rounds, and watched videos on how to neutralize tear gas. They left their phones at home so they couldn’t be tracked. They were preparing for brutality, yes—but not for war. War implies two armed sides.

“We started watching tutorials on how to protect yourself in a protest,” he says. “If you get tear gas, what you should do… Don’t take your phone; leave your phone at home. We learned about the precautions. We asked ChatGPT. No one in their darkest mind thought they would bring machine guns onto the streets,” Kazem said.

What he would go on to describe to me was nothing short of a blood bath. An unchecked, brazen, brutal assault on the citizenry by the very forces supposedly charged with protecting them.

Kazem has just fled Iran and spoke to Middle East Uncovered in a virtual interview. This is his story.

On January 8, Kazem went out with his wife to protest. Every kilometer or so, they would set a new meeting point in case they were separated.

“We were holding hands,” he said. “We couldn’t afford to lose each other.”

Kazem describes what protesters were trying to do in those early moments: disable cameras, silence propaganda, target symbols of state control. “We were part of the crowd that went for the TV… state TV complex,” he says. “People thought, let’s silence this regime. Let’s stop their propaganda. That way, they can’t lie and call us terrorists.”

They were, he emphasizes, “empty-handed. No guns, nothing.”

And then the regime arrived. What followed went beyond crowd control. The regime agents seemed to have been given orders to shoot to kill. He tells me about the trucks first—Toyota pickups with mounted machine guns. He saw them close enough to measure the distance in meters.

“I was 15 to 20 meters away from one of the trucks when he shot warning shots,” he says. “And the bullets are so powerful that they lit up the sky. They’re like fireworks, basically.”

In Rasht, a northern city where one of the deadliest massacres unfolded, witnesses told The Guardian they saw Toyota Hilux vehicles with machine guns move into the crowd, and that security forces fired on people fleeing burning streets.

Kazem’s account confirms that. They were being hunted.

“Why are they still shooting?” he remembers thinking on the second night. “We’re clearly running away.”

He tells me about a friend in Isfahan who ran with six others into alleyways as shots rang out. A motorbike with two men followed them—one driving, the other holding a gun. They turned. The bike turned. They ran again. The bike followed again. They hit a dead end and scattered behind whatever cover they could find.

And then the gunman fired into the alley and left.

The next morning, Kazem says, his friend went back and found a bullet embedded in the brick, and a spent casing on the ground. He kept it and made it into a necklace.

“He says, ‘I’m a dead man walking,’” Kazem tells me. “‘Here’s the casing of the bullet that was going to kill me.’”

Kazem tries to explain the feeling that haunted him most: that the shooters seemed incentivized, as if murder were a quota to be filled.

“It’s like someone says, ‘You know that man? If you shoot him, I’ll give you a million dollars,’” he says. “Or the more men you kill… I give you money. I can’t prove this, but it’s how it felt.”

He also described something more chilling than money: devotion.

“There are reports of them being foreigners, not even Iranian people,” he said—men he believes may have been recruited from militia networks supported by Tehran across the region. “So they are devoted to Khamenei himself,” he said. “They see him as the living imam of Shias.”

And then he added something that corroborates our reporting last week about regime agents “finishing” wounded protestors: “And you know about the reports that they walk amongst the injured… and give them a last bullet.”

Kazem tells me one story he did not witness directly, but that came from someone he trusts—his uncle, who went to see what remained after a machine gun was used in a small town in Isfahan province.

An individual on a motorbike, Kazem says, threw a Molotov cocktail toward one of the regime’s trucks and fled the scene. The soldiers, enraged, turned their heavy weaponry on the crowd.

“They pointed the machine gun at people and fired,” he says. “One bullet could pass through three people easily.” He described the guns as anti-aircraft weapons designed to bring down planes—being fired at people.

When the chaos subsided, the regime started scrubbing the evidence.

“They took the bodies away,” he says. “Cleared the evidence. They even washed the street. They washed the blood away.”

In the morning, his uncle went to the area and noticed that the once blood-red pavement was wet and clean.

“So it’s very clear that they washed the street,” Kazem says. “And my uncle saw parts of human bodies in the canal,” Kazem says, his voice tightening. “They were washed away from the street as if they were cockroaches.”

In Rasht, witnesses similarly described bodies being removed by dawn, with families later resorting to secret burials or struggling to retrieve remains due to fear of extortion. ABC News reported that internet and telephone access across Iran was cut on January 8, creating the longest digital blackout in the country’s history, with NetBlocks reporting outages lasting more than 400 hours. It still hasn’t been fully restored.

Kazem describes what that meant on the ground: isolation, rumor, and the sense that each neighborhood was being crushed one by one.

“With the internet shut down… people quickly figured out how to speak in code,” he says.

He and his wife ultimately left not only because they feared what might happen next (regime officers reportedly came to arrest participants after the fact, with many disappearing without any information about their whereabouts being shared with their families), but because they needed to keep working and required the internet to do so. And yet, Kazem tells me, the hardest part of leaving wasn’t distance from home.

“The hardest part is now we have access to the internet, and we can see there’s so little support,” he says. “There’s a huge lack of support for the massacre that happened in Iran. The same people who come out on the street and support people of Gaza… where are they?” he asks. “We’re human too.”

He isn’t asking for ideological conformity, but the lack of moral consistency enrages him.

“My countrymen didn’t die in a war,” he says. “Most people died defenseless on the streets where they grew up… at the hands of the armed forces that are meant to protect them.”

“I think I speak for a lot of Iranian people when I say… we just want revenge now with this regime,” he says. “We want them gone, but we also want revenge.”

He is careful to clarify that he doesn’t mean chaos or civil war, or weapons flooding the country. He doesn’t want to see what happened in Syria and Libya happen in Iran. He believes Iran is more cohesive than outsiders assume.

“I don’t think there’s going to be a civil war in Iran,” he says. “One, people don’t have guns. If we had guns, we would have fought back… Two, we don’t have anything against each other. Iran is the country of peace and love, trust me. Iran is the country of poetry. It’s not the country that supports terrorism. We’re not. And we are just so sick and tired of being called the number one terrorist supporter of the region.”

What he wants—what he believes many want—is targeted pressure against the regime’s repressive machine.

Then he says something that, to me, feels like quite the opposite of revenge.

“The love that exists among people in Iran is what holds this nation together,” he says. “What’s holding us… helping us to get through these hard times.”

Sanctions, he argues, crush ordinary people more than they restrain the regime. He lists the small humiliations outsiders don’t think about: the medication you can’t find, the cheap, unsafe cars you’re forced to drive, the impossibility of ordinary modern conveniences.

“There are things that are day-to-day ordinary things for you,” he says, “that’s a dream for an Iranian person.”

And still, he wants to go back.

“I feel like abandoning the ship is not what a good man should do,” he says. “We should stay… spread the love… enjoy the love that we give to each other.”

It is a beautiful sentiment, and also a tragic one, because it comes from someone who had to run for his life.

At one point earlier, Kazem compared the world’s silence now to Europe watching Hitler rise—an analogy that may sound extreme until you consider what it would feel like to be inside a country where the state is firing machine guns into crowds, washing blood from streets, arresting suspected dissenters indiscriminately, and turning off the internet to prevent images and testimony from leaving the country.

“We haven’t learned our lesson from history,” he tells me.

Maybe he’s right.

Or maybe the lesson is simpler, and more damning: that the world always learns—just too late, and at innocent people’s expense.

In the days since January 8th and 9th, the outlines of what happened have begun to emerge through satellite channels, leaked footage, phone calls on landlines, testimonies from people like Kazem who escaped, and the work of human rights groups trying to count the dead in the middle of a state blackout. In the coming days and weeks, we will continue to learn more about what really happened.

For now, Kazem is alive. He is safe. And he is speaking out. And he is doing it with the same dogged determination that has carried Iranians through decades of living under one of the most oppressive regimes in the world. He believes that if enough people tell the truth, the truth will eventually become harder to kill than the people who bear the burden of having had to carry it.

And maybe one day, Iran will truly be free.

Middle East Uncovered is powered by Ideas Beyond Borders. The views expressed in Middle East Uncovered are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Ideas Beyond Borders.