Iran’s Security Forces Accused of ‘Finishing’ Wounded Protesters

Witnesses allege suppressors in West Tehran were ordered to kill protesters by any means necessary. When live ammunition ran out, they turned to more violent, close-range methods.

As Iran’s December 2025–January 2026 protests reached their deadliest phase, witnesses and bereaved families described a chilling shift in tactics in a central-west Tehran corridor: fewer signs of live fire, and mounting evidence of pellet wounds followed by repeated knife or cleaver attacks.

Since late December 2025, Iran has faced countrywide protests followed by a sweeping and exceptionally violent crackdown. Compared with earlier waves, such as the “Woman, Life, Freedom” uprising (2022) and the Bloody November protests (2019), some activists and monitoring networks say the geography of casualties may have shifted, with reports suggesting higher numbers in parts of central Iran than in historically marginalized regions such as Baluchistan, Khuzestan, and Kurdistan.

At the same time, the overall death toll remains fiercely contested and exceptionally hard to verify under censorship, intimidation, and prolonged internet restrictions. Public estimates range from the authorities’ far lower figures to substantially higher counts circulated by medical networks and investigative reporting. TIME has suggested the number of victims was likely above 30,000, and The Guardian, citing its own research and sources, indicated a similar scale—claims that are difficult to independently corroborate in the absence of transparent access to forensic records, hospital data, and unrestricted reporting.

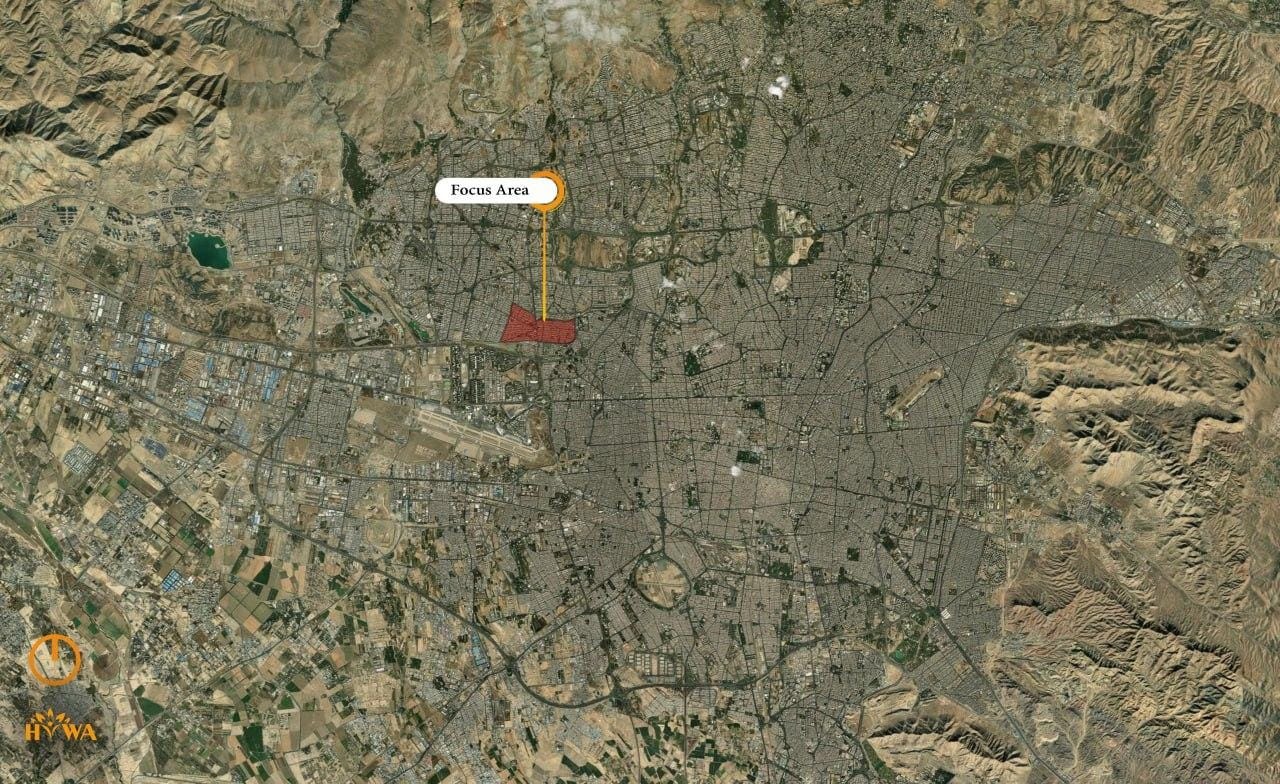

HIWA, a Washington-based human rights organization that documents alleged state violence, focused our investigation on a narrower—and particularly disturbing—set of allegations from one night in Tehran. During the countrywide digital blackout, multiple witnesses contacted our organization directly. Using Starlink connectivity, they described an unusual pattern of killing on Thursday, January 8th, in a west–central Tehran corridor around Ayatollah Kashani Boulevard, 2nd Sadeghieh Square, and the start of Sattar Khan Street. Witnesses alleged that specialized suppressive forces killed protesters with knives or cleavers—an account HIWA could not independently verify at the time because the internet shutdown severely constrained corroboration and access to evidence.

One of the cases brought to our attention is Aref Mousavi Dehshali, 33. According to relatives, Aref was originally from Dehshal village in Astaneh-ye Ashrafiyeh (Gilan Province). They recounted suppressors first shooting him in the leg with shotgun pellets, and then killing him at close range with sustained violence described as repeated knife and cleaver strikes. Relatives reported that the marks of blade strikes were clearly visible on his arms, hands, and legs, and that the number of separate stab wounds was especially striking. According to these accounts, Aref was killed at the end of Kashani Boulevard, near Esteghlal Park, and around 2nd Sadeghieh Square that night. His family also alleges that the Islamic Republic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Intelligence in Gilan later attempted to portray him as affiliated with the Basij (a paramilitary volunteer militia within the IRGC)—a claim the family firmly rejects.

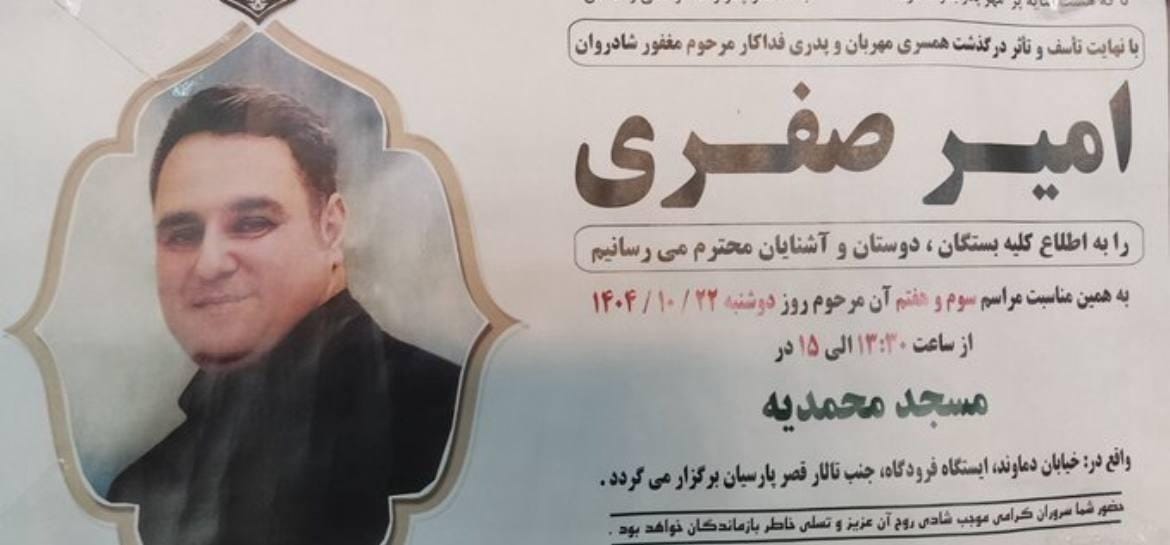

Another is Amir Safari, 46, a father of two children who, relatives said, ran a clothing shop in the Selsebil area of Tehran. According to accounts we received, Amir was detained on Sattar Khan Street on the same night. Witnesses told HIWA that as people surged forward attempting to free him, his throat was cut with a box cutter, and he was left on the ground amid the crowd. He reportedly died the following day, 9 January 2026. Two other victims were referenced in testimonies, but due to security concerns, we are withholding their names.

Eyewitnesses report that when live ammunition was depleted, the crackdown took a deadly turn toward deliberate, close-range violence.

The claim that live ammunition ran out cannot be independently confirmed. But the allegation matters because it suggests more than a change in weapon: it points to a deliberate move toward close-range “finishing” violence—a tactic that reduces the chance of rescue and increases lethality even when the initial injuries might not be immediately fatal.

Taken together, these testimonies and family accounts suggest a single, chilling inference: in that corridor, at those hours, state security forces behaved as if they had been ordered to kill protesters by any means necessary—even when live ammunition was reportedly no longer in supply.

These allegations demand sustained international attention. The accounts point to a form of repression designed to ensure lethality even when conventional means were exhausted, and to do so under conditions of blackout and fear that limit accountability. The international community can no longer plausibly claim uncertainty about the scale or nature of violence being used against Iranian protesters. The question now is whether governments, multilateral institutions, and human rights mechanisms will maintain scrutiny and pursue accountability—or allow silence and inaction to become accomplices to a campaign of repression that shows no sign of restraint.

Middle East Uncovered is powered by Ideas Beyond Borders. The views expressed in Middle East Uncovered are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Ideas Beyond Borders.