What It’s Like To Be a Political Cartoonist In Palestine

Mohammad Sabaaneh’s cartoons bear witness to life under occupation, resisting censorship to document the human toll of the war in Gaza.

“What It’s Like To Be” takes readers inside the lives of people working in remarkable and often demanding professions across the Middle East. Each installment offers an intimate look at the realities shaping their daily world. Look for WILTB in your inbox every Sunday morning.

As a political cartoonist in Palestine, Mohammad Sabaaneh does not need to search far for inspiration. His office in the West Bank looks out over Israeli settlements, and he passes through checkpoints every week.

A regular contributor to Palestinian newspapers and featured in publications worldwide, he is known for his raw, uncensored portrayal of the brutalities that have been normalized in occupied Palestine.

“As a Palestinian, you cannot be an artist just because you want to draw; everything is connected with our political situation,” he says.

Sabaaneh’s prolific output, which includes four books, keeps him in the public eye at a time when journalists are dying in record numbers in Gaza. According to Reporters Without Borders, more than 210 journalists have been killed by the Israeli army in the Gaza Strip since military operations began in October 2023, at least 56 of whom were “intentionally targeted,” the organization says.

Many of Sabaaneh’s friends and colleagues were among those killed in the war. The current conflict began on October 7, 2023, when Hamas massacred 1,195 people and took 251 hostage in Israel. “Each cartoon I have published since October 7 could be another reason to be killed or imprisoned,” he says.

Sabaaneh has already been incarcerated once. In 2013, he endured six months as a political prisoner in an Israeli detention center, an experience chronicled in his first book, Palestine in Black and White.

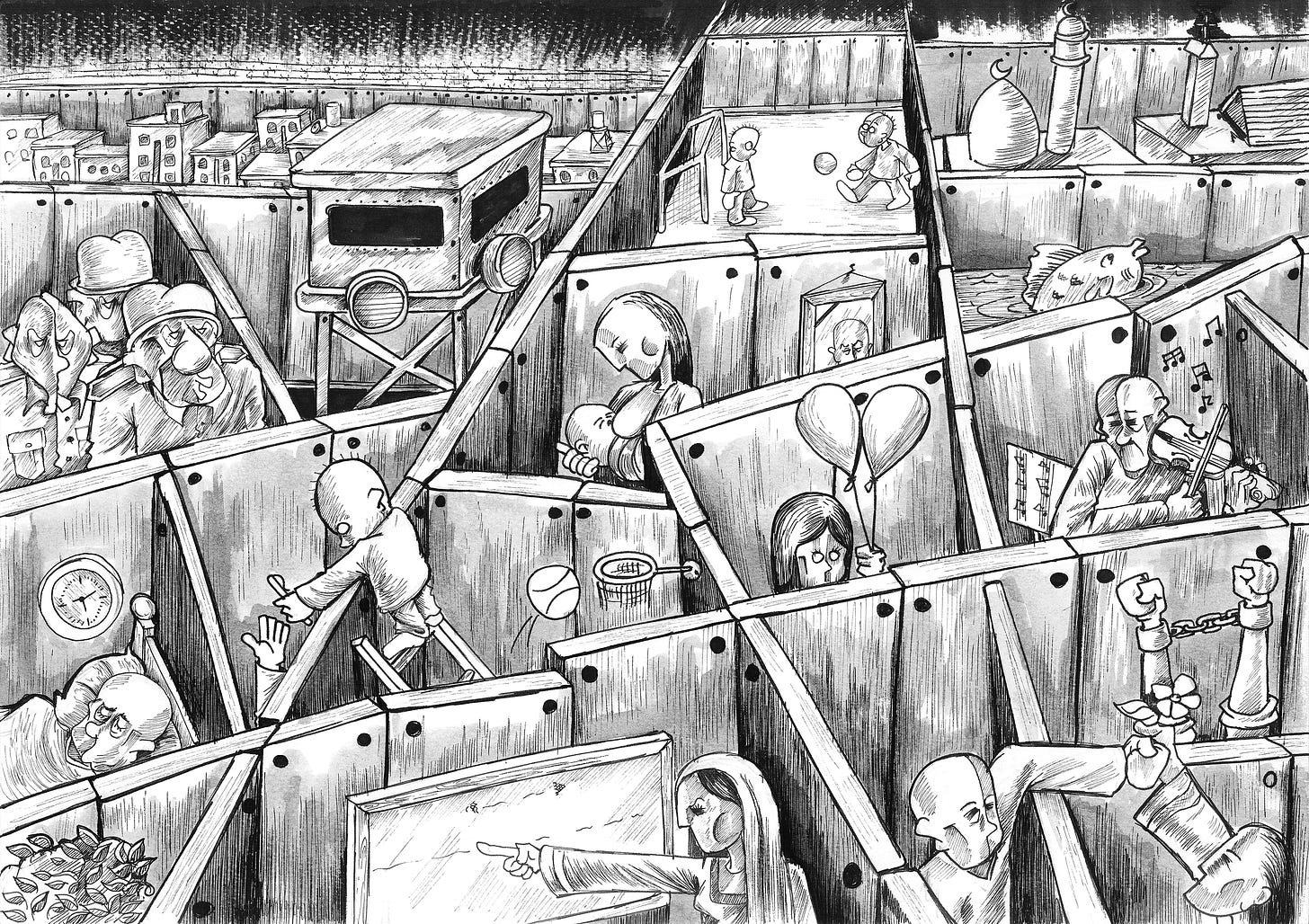

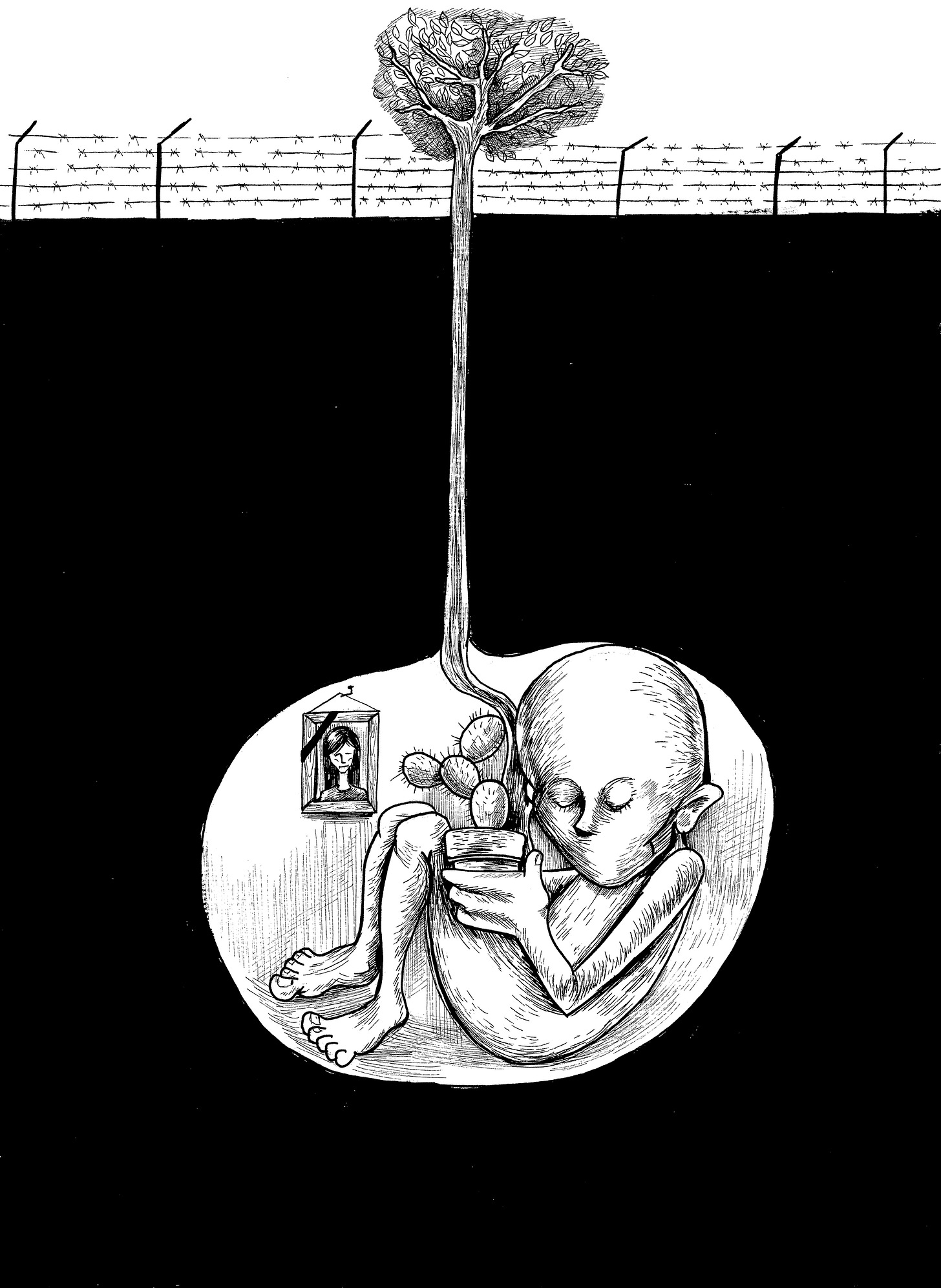

Prisons take many forms in Sabaaneh’s work, where concrete walls tower over children playing football, barbed wire encloses communities, and tanks hold families at gunpoint.

“Many Palestinian cartoonists are looking to glorify the Palestinian resistance, but I think my role is basically to convey these atrocities that people are facing inside Gaza,” he says.

A media blackout barring foreign and independent journalists from entering the Gaza Strip, except on escorted tours with the Israeli military, has severely constrained impartial reporting on the war. This restriction has global repercussions, shaping international narratives and fueling accusations of bias from all sides.

In the absence of live reporting, social media has filled the gap with voices on the ground in Gaza, but multiple reports of content moderation have pointed to disproportionate censorship of pro-Palestinian content on some platforms, including Facebook and Instagram.

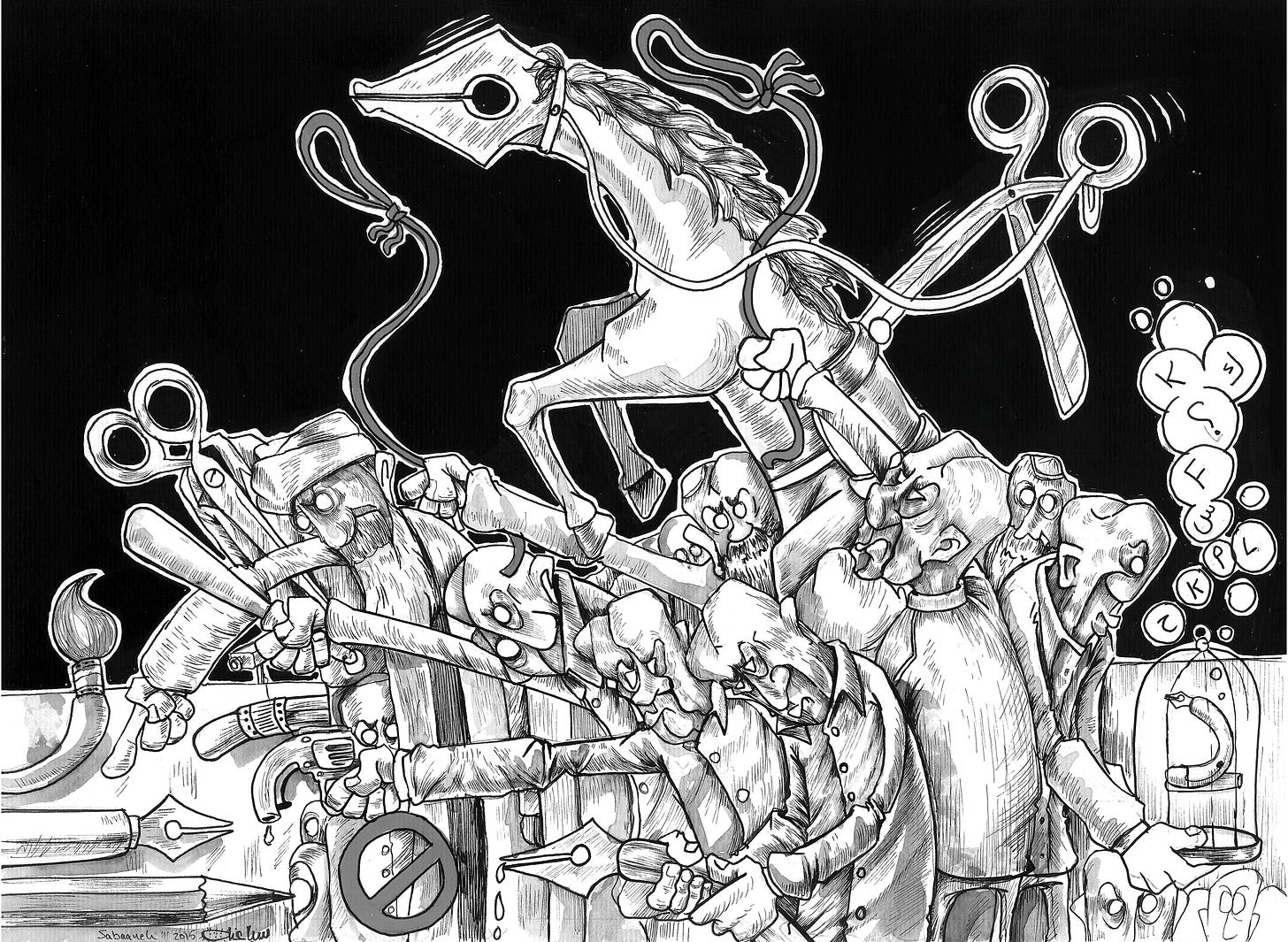

Censorship is a recurrent theme in Sabaaneh’s cartoons. In one striking image, freedom of expression withers in a world where pens are bound and broken, not just in Palestine, but across the Arab world.

The introduction to his first book references the region’s grim history of silencing outspoken illustrators, including the 1987 assassination of prominent Palestinian cartoonist Naji al-Ali in London.

Al-Ali was unflinching in his criticism of the situation in Palestine, and Sabaaneh has embraced this heritage. Born in a Palestinian refugee camp in Kuwait in 1978, he learnt about Palestine from Ali’s illustrations, before moving to Jordan and then the West Bank, where he began working as a cartoonist in 2002.

For those outside the orbit of Middle East media, Sabaaneh’s output offers a crash course in the symbols of suffering that articulate Palestinian reality. Gaunt, mouthless figures appear tethered and chained, trapped behind high fences and crushed beneath booted feet. Many are children denied the chance to flourish in a barren landscape where saplings are denied the opportunity to grow.

For the youth of Gaza and the West Bank, there is no escape. One young boy stands forlorn before an impassable ladder propped against the wall separating Israel and Palestine. Others are dragged past lifeless bodies by shadowy soldiers or entombed in concrete prisons, surrounded by the weapons of war.

From his tiny cell in solitary confinement, Sabaaneh traced these images into the air until he was able to steal paper from a guard and fill it with the horrors he had witnessed. Every time prisoners were released, he smuggled out sketches, hoping to show the world what life in Palestine is really like.

Capturing these moments was also a way of staying sane in a degrading environment. “I was ugly in prison,” says Sabaaneh, who filed his nails against cell walls to reclaim some semblance of humanity.

The final section of the book narrates this experience—the preordained sentence from a faceless judge, the pain of separation from loved ones, and the truth behind the romantic portrayal of political prisoners.

“In detention, I got to know my heroes and witnessed their agonies,” Sabaaneh writes. After that, he stopped glorifying Palestinian resistance fighters because “you dehumanize them when you just depict them as a superhero.”

Risking re-arrest, or worse, Sabaaneh refuses to be silenced. In 2022, he lost 15 years of content after his social media accounts were blocked. Three years later, he used the experience to inform his latest book.

In 30 Seconds from Gaza, Diary of a Genocide, published in 2025, he draws on social media footage from the war in Gaza. In Sabaaneh’s hands, these fragments of evidence are preserved for future generations, resisting attempts to rewrite history and wipe the truth away.

Penned in indelible ink, these cartoons feature identifying details that anchor their sources in reality. One illustration, from October 15, 2023, shows “A child screaming after the martyrdom of his father,” while a drawing of the previous day shows “A child carrying a small bird with him during displacement.”

Speaking at international events, Sabaaneh is sometimes surprised to see audience members cry. Palestinians are hardened to conditions others find unimaginable— “we became sick with this situation,” he says.

Sabaaneh’s work has earned him global acclaim. In 2017, he was awarded the Prix d'Or at the Marseille International Cartoon Festival, and in 2024, he received the prestigious Swedish EWK award.

But with recognition comes more attempts to muzzle him. Trips get canceled and speaking invitations are rescinded, often with no explanation.

In 2024, a board member resigned from the Lakes International Comic Art Festival (LICAF) in the UK over Sabaaneh’s involvement in the program. In this instance, the festival upheld his invitation. “That was a victory for freedom of speech,” he says.

Sabaaneh shrugs off accusations of anti-semitism as attempts to silence his commentary on the Israeli government’s actions in Palestine.

“I know I am not anti-semitic, my friends around the world are Jewish. It is our right as Palestinians to criticize this situation,” he says.

Abroad, he is reminded what ordinary life looks like, a life his daughter, 11, and son, 7, often ask about. At home in Ramallah, it’s easy to find meaning in his mission to document Palestinian suffering. But in Europe and the US, he sees how other children live.

“Like any parent, I want to raise my kids without telling them about the occupation, but unfortunately, we cannot. Everything connected to the occupation.”

Even so, he cannot countenance a life elsewhere. Since the war in Gaza, the number of political cartoonists in Palestine has dwindled, and Sabannah feels more than ever that he must remain, despite the risks.

Teaching at the Arab-American University in the West Bank, he advises young people to prioritize safety. “It’s not a target to be a prisoner. If you can keep working and conveying the voice of our people, that’s our victory,” he says. It’s a victory Sabaaneh claims with every cartoon, refusing to relinquish his right to speak out. Amid the media blackout on Gaza, his is one of the few voices that still breaks through, forcing the world to look, when it would rather turn away.

Middle East Uncovered is powered by Ideas Beyond Borders. The views expressed in Middle East Uncovered are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Ideas Beyond Borders.