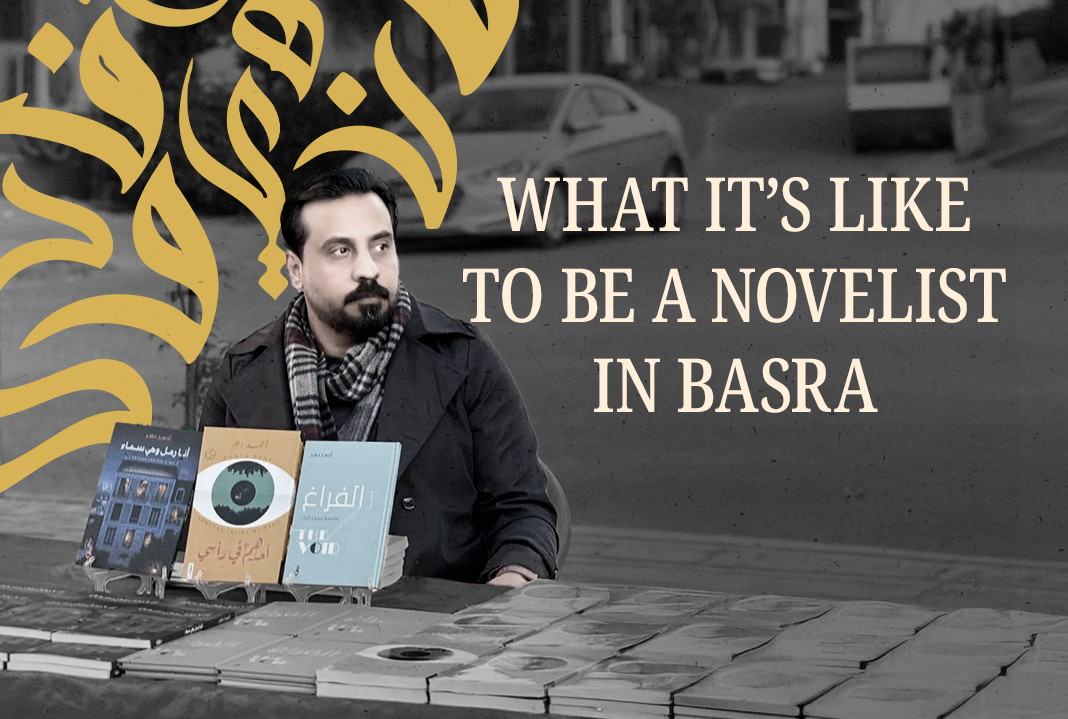

What It's Like To Be a Novelist in Basra

As his city contends with corruption, decay, and a declining reading culture, one novelist continues to challenge his society through fiction—despite knowing how few will read him.

“What It’s Like To Be” takes readers inside the lives of people working in remarkable and often demanding professions across the Middle East. Each installment offers an intimate look at the realities shaping their daily world. Look for WILTB in your inbox every Sunday morning.

Life for a successful writer can be isolating in Iraq. Authors may still be respected, but in a society that reads less and less, they have become increasingly invisible. “It’s not like the West, where a popular author might reach millions. The author in Iraq is read by a few hundred people,” says novelist Ahmed Daher.

Daher is one of Basra’s most eminent novelists, but few people recognize him in the street. This matters because Daher writes to air his views, exploring the issues of the day through a fictional lens. “I want to share what I write with the world,” he adds.

While many Iraqi authors self-censor to avoid alienating readers, Daher embraces difficult topics. His first novel, Al Jawf (The Void), confronts underage marriage, a sensitive subject in Iraq, where around 7 percent of girls are married by the time they turn 15.

Debate has surged recently over legislation allowing girls as young as nine to marry and the risks posed to women and girls by the thousands of unregistered marriages performed by religious leaders each year.

Daher’s novel speaks about the suffering of the fetus in the womb and of the young mother married to an older man. It’s sensitive ground and draws on deep divisions around social customs that allow this practice to persist. But despite the contentious subject matter, Daher’s story was largely well-received.

It’s still his best-selling work, particularly among female readers, who praise its honest portrayal of their experiences.

When he does receive criticism, he welcomes it “in a sportsmanlike manner,” as he does all feedback. “Objection is a positive thing for the writer; it is proof of reader engagement,” he says.

This is particularly pertinent for Daher, who worries about declining reading rates in the age of the internet. As social media replaces books for many Iraqis, he fears people are losing the ability to distinguish fact from fiction.

“In Iraq, we have seen how slogans can turn into a new religion, and how reason can be replaced by chanting. Reading is the only defence against this tide,” he says.

Iraq was once a country of readers—the land where writing was invented and home to some of the greatest libraries in history. Famous among these was the House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Ḥikmah), founded in the ninth century at the dawn of the Islamic Golden Age.

It was an age of intellectual discovery as the Arab world pioneered advances in the arts, science, maths, astronomy, and many other fields. The ruling caliphs amassed huge collections of books from across the world, translating ancient Greek, Persian, Indian, and Syriac texts into Arabic.

Today, these libraries are long gone, but their legacy continues to inspire a community of bibliophiles in their effort to spread knowledge and inspire Iraqis to keep reading.

“Reading, good reading, would change a lot. People here would be more open-minded, liberated from the influence of sectarianism and tribalism. This city would be a better place,” Daher says.

Basra has seen its share of power struggles. The largest city in southern Iraq was once a beautiful place to live, but recent decades have seen it deteriorate as corrupt political factions and rival militias vie for control over the region’s oil reserves.

Meanwhile, public grievances over acute water and electricity shortages, failing infrastructure, and chronic unemployment are sidelined. This should be one of the wealthiest provinces in Iraq. Instead, it is one of the poorest, its riches siphoned off and sent elsewhere.

Long before oil, the city’s wealth came from the sea. Home to Iraq’s only port, Basra was a hub of trade during the Islamic Golden Age, drawing merchants, scholars, and artists from across the region to participate in a vibrant cultural scene.

Remnants of this spirit were still visible before the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s, but conflict, corruption, and the toxic imprint of oil have left the city lifeless. These days, sewage clogs the canals, mingling with rubbish and industrial waste in a fetid symbol of Basra’s decline.

Reckoning with these changes has provided the impetus for Daher’s new work. The turbulent events of the last 25 years in Iraq have fuelled his literary output, but the 39-year-old feels he still has “a lot to accomplish.”

Moving through the city, he finds its proximity to the sea reassuring. “It gives me a sense of openness in an otherwise landlocked country.” On days when the words refuse to flow, he walks along the banks of the Shatt Al Arab River to free his mind. “Writing is never easy. I put all my energy into it,” Daher says.

Writing at home can be a challenge with four children aged four to 14, so he waits until after midnight, when the household falls silent.

Then, he opens his laptop and plays soft piano music, allowing his thoughts to slow and settle into words. “I’m not someone who seeks out ideas. I write when inspiration comes,” he says.

When writer’s block hits, Daher turns to books, finding his way back to writing through the words of Amin Maalouf, Naguid Mahfouz, Herman Hesse, Carlos Zafon, and Jose Saramago.

For him, reading is essential. “I read to remember that I am not alone, that what I endure here in Basra echoes elsewhere in the world,” he says.

He first felt that connection as a child discovering the tales of One Thousand and One Nights. The stories, collected across centuries and compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age, fascinated Daher and set him on the path to becoming a writer.

Among them are the adventures of Sinbad the sailor, who is said to have set sail on his voyages from the shores of Basra. What Daher liked most was the storyteller Scheherazade, who weaves a new tale into the collection each night. “It was like a maze of doors, each opening onto another door,” he recalls.

Daher’s parents welcomed their son’s voracious reading habits but told him he could never rely on his income as a writer. They were “absolutely right,” says Daher, who works as a high school economics teacher and writes on the side. “Writers cannot make a living being writers in the Arab world,” he says.

He has now set himself the formidable task of writing a trilogy to cover Iraqi history from 1912 to 1945. Beginning in the final days of the Ottoman Empire, he frames the shifts of the twentieth century within a fictional narrative set in Basra. “I am trying to open a window to a past that could have changed the future for the better,” he says.

It’s an ambitious project that demands extensive research and more time than he can currently give. Juggling the roles of father, writer, and teacher, it’s tempting to wait for the right moment, but looking at the city around him, the frustration of its youth and the decline they are caught up in, he feels compelled to pass on these lessons. Whether people listen is another matter.

“There’s a lot of good writing out there, but good writing won’t bring change. Rather good reading can change the future, but first people need to be persuaded to read,” he says.

Middle East Uncovered is powered by Ideas Beyond Borders. The views expressed in Middle East Uncovered are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Ideas Beyond Borders.