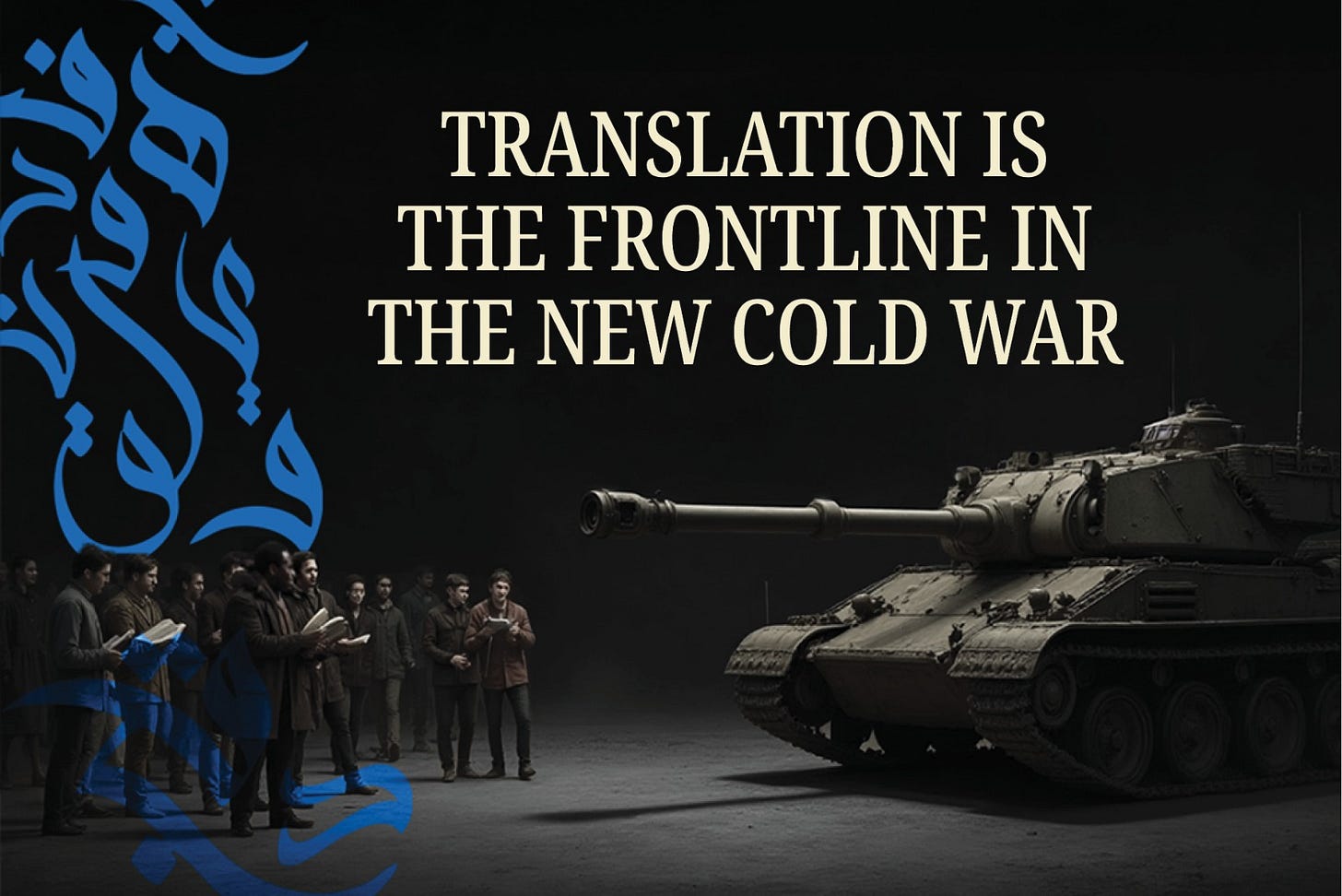

Translation Is the Frontline in the New Cold War

Who controls the language of ideas will shape the future of thought and artificial intelligence

It’s often said that civilizations fall not through war or famine alone, but through the erosion of ideas. But ideas don’t travel on their own—they must be translated first. For those who believe in soft power, translation isn’t a cultural nicety. It’s a strategic imperative.

Today, the ideological battlefield has shifted. The Cold War’s missiles have been replaced by algorithms. Influence isn’t just broadcast over the radio or printed in pamphlets—it’s encoded into artificial intelligence. And once again, the decisive factor may be who takes the task of translation seriously.

The modern West owes its intellectual foundations not only to ancient Greece and Rome, but also to the Arab scholars who refused to let those legacies die.

During the Islamic Golden Age, from roughly the 8th to 13th centuries, cities like Baghdad, Damascus, and Cordoba became global centers of learning. In Baghdad, the House of Wisdom employed scholars who painstakingly translated Greek scientific, philosophical, and medical texts into Arabic. This wasn’t mere preservation; it was reinterpretation. The Arabic versions of Plato and Aristotle were studied, commented on, and enhanced. Thinkers like Avicenna and Averroes didn’t just transmit knowledge; they transformed it.

When Europe began to stir from its intellectual slumber during the Renaissance, it did so largely through these Arabic texts—translated back into Latin by scholars in Sicily and Spain. In other words, the West was rebooted through translation.

That historic moment reminds us: the direction of influence can shift. The act of translation can be revolutionary. The guardians of knowledge are not always those who originate ideas, but those who keep them alive.

Centuries later, the Soviet Union understood the power of translation just as well.

At the height of the Cold War, the USSR executed a vast ideological campaign that spanned continents and languages. Moscow-funded publishing houses churned out Marxist-Leninist literature in Arabic, Persian, French, Spanish, and Swahili. Radio Moscow broadcast anti-capitalist programming across the Middle East and Africa. The Soviets even translated comic books and children’s stories that painted the United States as exploitative and morally bankrupt.

It was a brilliant soft power strategy. While the West focused on military alliances and economic development, the Soviets embedded their ideology in schools, bookstores, mosques, union halls, and universities. They gave the Global South the vocabulary of class struggle and imperialism—and with it, a sense of belonging to a global ideological movement.

Generations across the Middle East, Latin America, and sub-Saharan Africa grew up fluent in the language of socialism. Words like bourgeoisie, dialectics, and proletariat became familiar—romantic, even. Meanwhile, ideas like individual liberty, limited government, and free markets remained untranslated, misunderstood, or missing entirely.

The ideological imbalance still lingers. In many parts of the Arab world, capitalism is viewed with suspicion—not because people read Adam Smith and found him unconvincing, but because they never read him at all. In Arabic, there is still no natural-sounding equivalent for phrases like “spontaneous order” or “regulatory capture.” Translators often resort to clunky explanations or metaphors that lose the precision and power of the original.

This isn’t a failure of intellect. It’s a failure of access. You can’t debate ideas you don’t have. And without translation, you don’t have them.

The liberal tradition—from John Locke to F.A. Hayek to Deirdre McCloskey—remains largely absent from the intellectual bloodstream of much of the world. Not rejected. Just unavailable.

We are now entering a new phase of ideological competition—one that revolves around artificial intelligence.

Unlike the Cold War, today’s contest doesn’t hinge on tanks or territory. It hinges on training data. In an AI-driven world, what matters most is what an algorithm learns—and from whom. That means the corpus of translated knowledge has never mattered more.

The analogy goes like this: two people are bathing in a river when a tiger appears. One sprints away naked. The other hesitates, trying to put on clothes and shoes. The one dressing yells, “You can’t outrun a tiger barefoot!” The runner replies, “I don’t have to outrun the tiger. I just have to outrun you.”

That’s the nature of today’s AI arms race. It’s not about being perfect, it’s about being faster than your competitors in defining the intellectual terrain.

In China, AI models are trained on state-approved content. They avoid politically sensitive topics, reinforce official narratives, and sidestep any mention of democratic movements or minority repression. These models will shape the online experiences of billions—not just in China, but in any region where Chinese tech becomes dominant.

Western models like ChatGPT or Grok are built on broader datasets. But even they are skewed toward English and a narrow band of Western thought. In Arabic, Persian, or Urdu, they reflect the absence of translated liberal texts. If the only content available in those languages comes from old socialist tracts or religious dogma, then that’s what AI will learn and repeat.

AI doesn’t have an ideology. But it has a memory. And its memory is made of words.

This is where we are most vulnerable. If we want AI systems to reflect pluralism, freedom, and open inquiry, we must start with translation. Not someday. Now.

We must invest in translating foundational works of liberal economics, philosophy, political theory, and science into the languages that have been neglected for decades. Arabic, Kurdish, Persian, Pashto, Urdu, Dari—these are not linguistic backwaters. They are spoken by hundreds of millions. They deserve access to the full range of human thought.

Because once an idea is translated, it can be debated. Once it is debated, it can evolve. And once it evolves, it can shape the future.

This is not about cultural outreach or charity. It’s about intellectual sovereignty. It’s about giving the next generation in the Middle East, Central Asia, and beyond the tools to think critically. Not just about the West, but about themselves.

The Cold War may have ended with the fall of the Berlin Wall, but the war of ideas never stopped. It just changed platforms. Today’s battlefield is digital. The battalions are datasets. And the ammunition is words.

If we want freedom to mean something in the 21st century, we need to speak its language in every corner of the world. That means funding translators, building open-access archives, and training AI on texts that uphold liberty and critique it.

We must stop treating translation as an afterthought—and start treating it as what it really is: a frontline in the new Cold War.

Middle East Uncovered is powered by Ideas Beyond Borders. The views expressed in Middle East Uncovered are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Ideas Beyond Borders.