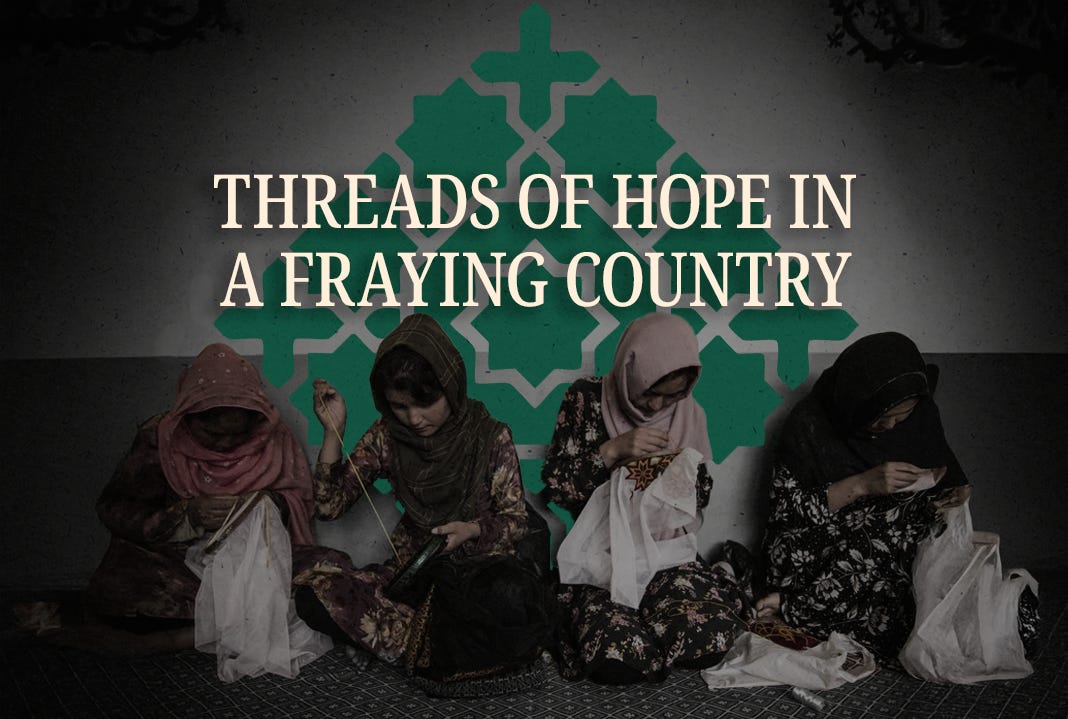

Threads of Hope in a Fraying Country

As Afghanistan’s economy collapses and restrictions tighten, a revival is taking place behind sewing machines and workbenches. One French designer is helping Afghan women reclaim their independence.

It started with a pair of earrings. They were typical of the kind once seen in souqs across Yemen, where families purchase matching jewelry sets to mark special occasions, investing in intricate pieces to hand down through generations.

The secrets of the craft are shared from father to son, nurturing long family lineages of talented artisans and building Yemen’s reputation as home to the finest filigree.

In Belinda Idriss’s case, the earrings came from her mother, along with a warning. “She told me the craft sector in Yemen was once flourishing, but a lot of these beautiful traditions have disappeared,” Idriss said.

“If we don’t preserve these techniques and start doing everything by machine, then this knowledge is all going to disappear.”

Years of conflict combined with modern methods of mass production have devastated Yemen’s craft sector, undermining family businesses and making traditional skill sets redundant. It’s a problem replicated across the global south, where crafts are being sidelined, often with no replacement for the gap they leave in local economies.

The impacts are most acute in hostile environments, where communities have been scattered by displacement. Yet these traditional skills, honed over generations, can be a vital means of survival for communities living in unstable or restrictive societies.

They also provide a route for women to work, offering a rare path to financial independence in countries with limited employment opportunities.

In Afghanistan and Palestine, where Idriss runs multiple projects, tailoring and embroidery have traditionally been a cornerstone of communities, providing a vital source of income while contributing to the preservation of cultural heritage.

“After October 7, many Palestinian employees lost their permits to enter Israel. The only way to get a livelihood was for women to go back to embroidery to put food on the table,” Idriss said.

“The same pattern is happening in other countries, too.”

In Afghanistan, where the Taliban has imposed mounting restrictions since taking power, craft is one of the only sectors that remains open to women.

After hearing her mother’s stories about life in Yemen before the war, Idriss began researching how craftsmanship could address some of the socio-economic issues in countries across the global south. “Craft has been very underestimated for many years, but with all the conflict in this part of the world, we have seen a recurrence of interest in these activities,” she said.

In March 2021, she landed in Kabul, Afghanistan, to volunteer with a local fashion brand. Her goal was to explore how traditional crafts could address socio-economic issues and create livelihoods that would endure in turbulent times. What she couldn’t know was how soon her ideas would be tested.

Six months later, her new home collapsed into chaos.

In the months after the Taliban takeover that August, the Afghan economy imploded as foreign aid halted and the banking system froze. Unemployment spiraled and poverty engulfed the country, leaving many Afghans struggling to meet basic needs.

The Afghan artisans Idriss learned alongside lost their jobs. Skills that could sustain families were being snuffed out just as they were needed most.

“In times of war or crisis, when displacement and destruction erase landscapes and homes, the handmade object becomes both a livelihood and a cultural lifeline,” she said. “It is an act of resilience and survival. Craft carries memory, identity, and continuity. Anchoring communities when everything else feels uncertain.”

For Idriss, the task ahead was straightforward. She spent a month raising funds in Europe, then travelled back to Kabul in late September.

As businesses closed and revenue streams dried up, she launched projects to support Afghan artisans working in woodcarving, glassblowing, jewelry, and embroidery before launching the Darya project to train and employ 20 female tailors.

She later set up Artijaan, a social enterprise that functions as a business, channelling profits back into the project to help a growing number of Afghan women find work in the sector.

“We provide the starting kit and all the tools, but they have to do the work,” said Idriss, who draws a sharp distinction between Artijaan and charities, many of which left Afghanistan when the Taliban took over.

“In the past, there was a lot of dependency on humanitarian aid in Afghanistan, but after the fall, these initiatives just stopped because they weren’t sustainable,” Idriss said.

The closure of USAID, alongside wider cuts to development funding, has reinforced the need for projects like Artijaan to function independently.

“Aid is important, but it really has to be done in a way that is mindful, with the objective of making the beneficiary as independent as possible from external support,” Idriss said.

“It should be capacity-building and provide support like raw materials, machinery, and microloans.

At the Artijaan workshops, women work on orders for the brand’s point of sales in Europe. Standards are exacting. Each item must pass stringent quality control checks before it’s cleared for sale.

“We tell them this has to function on profit, we cannot rely on grants,” Idriss added.

Changing the mindset proved difficult at first. Customers returned products, citing flaws and inconsistencies. So Idriss doubled down on training, explaining that to be sustainable, Artijan needed to adopt the same exacting standards as international fashion brands.

That hard work is now paying off. Artijaan has a reputation for quality products and beautiful designs, selling shirts for up to $250, and collaborating with fashion brands in Europe.

Even amid economic stagnation and rising unemployment in Afghanistan, the project has continued to grow, expanding from 10 to 1,000 women in seven provinces across Afghanistan.

Afghan women have typically worked as seamstresses and embroiderers, but Artijaan is training them to become tailors too, a role traditionally occupied by men in Afghanistan.

“Some of the women are supporting their whole family with this work, so it’s a source of pride,” Idriss said.

It’s also an opportunity to get out of the house and escape the restrictions that govern their daily lives. Artijan operates with permission from Taliban authorities, and is subject to regular inspections to ensure their rules are enforced, including gender segregation in the workplace.

One local governor in the northeastern part of the country has even asked Idriss to expand the project to help more women find sustainable work. “I think he realized it was bringing more peace to the communities by giving this right to women,” she said.

In the aftermath of a sudden internet and mobile shutdown at the end of September, when authorities imposed a 48-hour telecommunications blackout on Afghanistan, people are more aware than ever of the few rights that remain. Women and girls working or studying online saw once again how quickly their lives could worsen as another door slammed shut.

But amid the click and hum of sewing machines on the workshop floor, opportunities remain. For the women working at Artijaan, it’s not just about earning an income or keeping traditional crafts alive. This work offers a safe space to cultivate new skills and a rare thread of stability in uncertain, frightening times.

Middle East Uncovered is powered by Ideas Beyond Borders. The views expressed in Middle East Uncovered are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Ideas Beyond Borders.