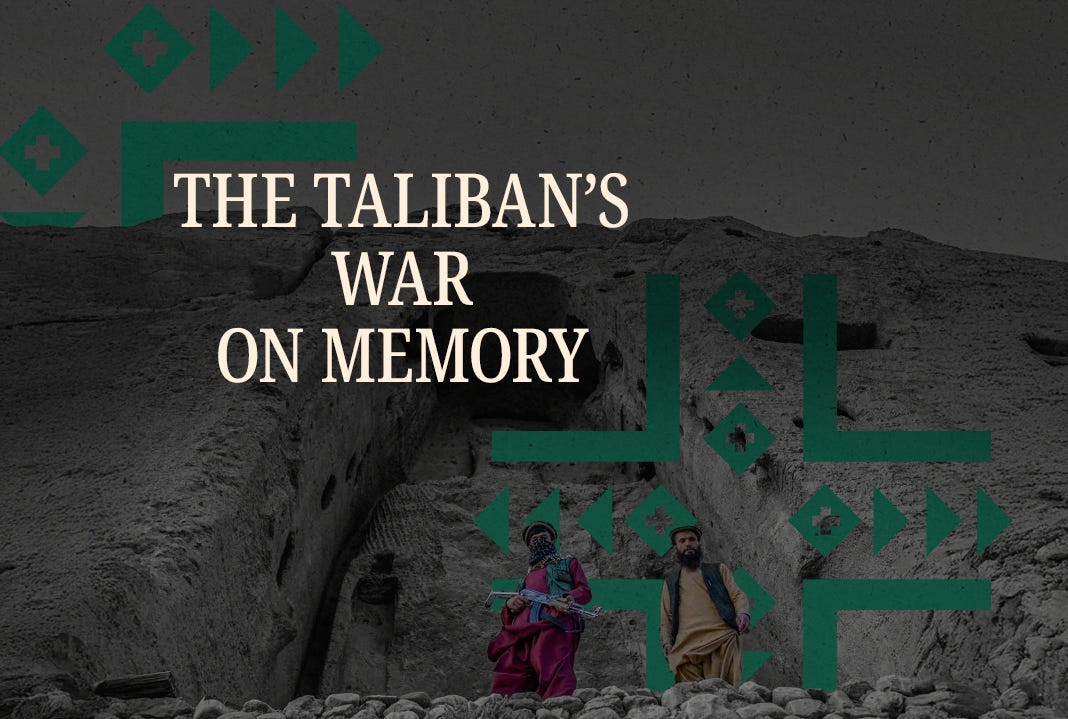

The Taliban's War on Memory

From Bamiyan to Mes Aynak, the Taliban are waging a campaign of cultural erasure—an assault on Afghanistan’s past and a crime under international law.

In Afghanistan, the struggle is not only for power over land or people but also for control of memory itself.

The Taliban have long understood that to dominate the present, you must curate the past. Their rule since 2021 has been marked not only by political repression but also by a systematic assault on cultural heritage. What is destroyed, what is neglected, what is rebranded: these decisions shape what people in Afghanistan are allowed to remember. Under international law, the deliberate erasure of monuments, statues, and sites is not an aesthetic matter. It is a crime under the Rome Statute. It states, “all peoples are united by common bonds, their cultures pieced together in a shared heritage and concern that this delicate mosaic may be shattered at any time.”

When they swept into Kabul in August 2021, the Taliban made their intentions clear. Within days, fighters in Bamiyan blew up a statue of Abdul Ali Mazari, the Hazara leader they had executed in 1995. And they didn’t stop there. They replaced it with a stone replica of the Koran, making their vision explicit: religion authorized by their interpretation would usurp all plural memories. This was an unmistakable act of cultural domination, carried out in the same province where two decades earlier the Buddhas of Bamiyan were blown apart.

The Taliban’s vandalism is not limited to statues. In April 2023, researchers reported that Dilberjin, the largest ancient city in northern Afghanistan, had been systematically looted between 2019 and 2021, with pillage continuing under Taliban control. In 2022, unsanctioned excavations took place in the Bamiyan Valley caves, a UNESCO World Heritage site. These were carried out by professional smugglers, but in Taliban-held territory. The regime has turned a blind eye, allowing international traffickers to strip Afghanistan’s heritage and sell it to the highest bidder.

In July 2024, reports from Kabul showed Taliban fighters drilling into the statue of Abdul Ali Mazari in the Pul-e Sokhta area. Then in August 2025, in Mazar-e Sharif, the Taliban removed and destroyed a statue of Ali Shir Nava’i, the fifteenth-century Turkic-Persian poet. The demolition of his statue was another deliberate insult to Afghanistan’s plural history, a message that non-Pashtun culture could be erased from public space. After a public outcry, the Taliban muttered about rebuilding it, but the destruction had already done its work.

Looting and neglect go hand in hand. A 2024 BBC investigation, using satellite evidence, showed archaeological sites bulldozed and systematically looted since the Taliban returned to power. Ancient settlements stripped. Statues smuggled. Vandalism at Bamiyan itself. It is systematic, intentional plunder happening under their watch.

Neglect is another weapon. Encroaching construction projects, unmanaged tourism, and a lack of preservation resources are leaving priceless heritage sites to collapse. The Bamiyan Valley, already mutilated by the Taliban in 2001, is now crumbling under their indifference. What they do not actively destroy, they are content to let rot. Destroying a society’s culture, heritage, and history is not just an attack on objects. It silences a nation. You become nothing. You are nothing.

International law makes no distinction between destruction by dynamite and destruction by neglect. The 1954 Hague Convention obliges those in power to safeguard cultural heritage. Customary international law classifies it as a protected civilian object. The Rome Statute defines intentional attacks on historic monuments as war crimes. The ICC’s Timbuktu judgment in 2016 established that destroying heritage is an assault on human dignity itself. By every measure, the Taliban are in breach.

Nowhere is this clearer than at Mes Aynak. This 2,000-year-old Buddhist city south of Kabul is one of the richest archaeological sites in Central Asia. It is also one of the world’s largest copper deposits. For years, archaeologists have begged for it to be saved. But in 2023 and 2024, the Taliban signed deals with Chinese state-owned companies to mine it. That means bulldozers over monasteries that chart Afghanistan’s ancient past. To trade away Mes Aynak is licensed destruction, this time dressed up as development.

The international community should recognize this for what it is. Not only a human rights abuse but a crime under international law.

Documentation is essential. Every defaced statue, every looted site, every bulldozer caught on satellite is evidence. The Hague has already shown that perpetrators of cultural destruction can be convicted. The challenge is to ensure Afghanistan’s losses are not dismissed as internal matters.

Cultural heritage belongs to humanity as a whole. Its erasure by the Taliban is not just Afghanistan’s tragedy. It is a crime against all of us.

Middle East Uncovered is powered by Ideas Beyond Borders. The views expressed in Middle East Uncovered are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Ideas Beyond Borders.

👏🏻👏🏻👏🏻

Even the name 'Afghanistan' privileges the Pashtun minority, as 'Afghan' is historically synonymous with Pashtun-speaker. Pashtun-supremacists must be exposed for erasing Persianate, Turkic, and non-Islamic culture from the country's historical record.

The only reason a centralized 'Afghanistan' was cobbled together in the 19th century was as a buffer state between the Russian and British-Indian empires.

The Non-Pashtun majority in this country must have their rights to self determination respected. Not by military intervention, but by sponsorship of a federal, decentralized and truly democratic state.