The Life of an Iraqi Jew in Exile

Born into one of the world’s oldest Jewish communities, Edwin Shuker fled Baghdad as a child. Decades later, he has become a bridge between Jews and Arabs, and a guardian of a fading history.

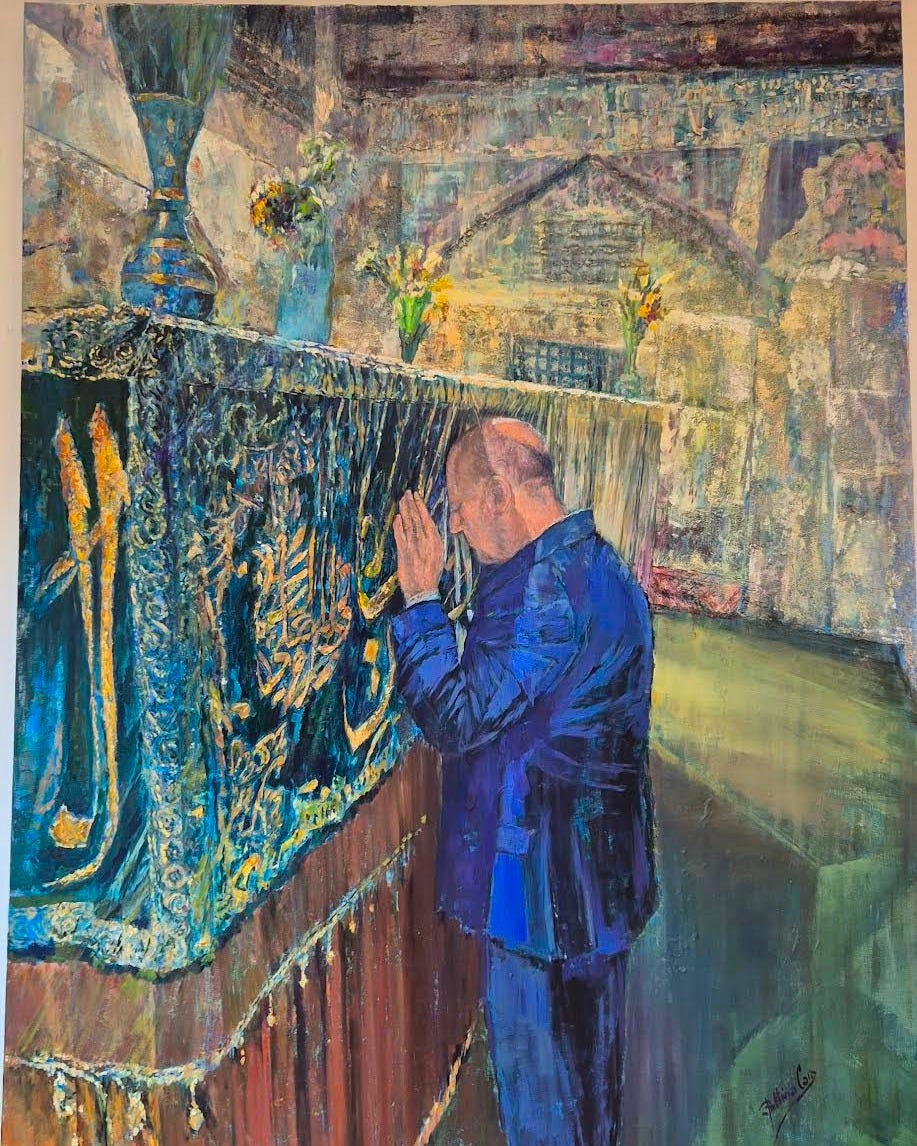

There’s a grand painting of Edwin Shuker that hangs in his living room. Visually opulent, it shows him praying before the tomb of the prophet Ezekiel in Iraq.

Located within the Al-Nukhailah Mosque complex in Babylon province, the tomb is draped in an emerald-green cloth embroidered with the words “peace be upon Ezekiel” in golden Arabic.

The intensity of Shuker’s prayer can be felt thousands of miles away here in England.

How he gained access to the site “was a miracle,” he says, smiling.

We meet in his north London home, which he shares with his wife Esther, over coffee and a baklava made by his 93-year-old mother, who lives nearby. The outgoing vice president of the Board of Deputies of British Jews, the 70-year-old is a leading figure among diaspora Jews.

But the story he wants to share begins long ago, in a Baghdad that no longer exists.

The eldest of three children, Shuker was born in Iraq in 1955 to one of the most ancient of all Jewish communities. Jews had lived in Babylon since the 6th century BC, after being exiled from the Kingdom of Judah. Even when the Persian king Cyrus the Great later allowed them to return, many stayed, establishing communities that flourished for over 2,500 years.

By the time Shuker was born, Iraqi Jews were woven into the fabric of the country. His family lived in relative prosperity—they even had a butler. The first eight years of his life were “paradise.” No one felt different, he insists, until much later.

There were, however, moments of upheaval and persecution. The Farhud massacre was a Nazi-inspired pogrom that erupted in Baghdad on June 1, 1941—some 180 Jews were killed and thousands injured. Within a decade, most Iraqi Jews emigrated to Israel. The creation of the Jewish state in 1948 also led to more violence.

Most of Shuker’s extended family fled. The intention was to join them in Israel eventually, but when the Shukers heard “they were living in refugee camps,” they stayed put.

Slowly but surely, that paradise started unravelling after 1963, when a coup led by the nationalist Ba’ath Party overthrew and executed Prime Minister Abd al-Karim Qasim. Jews were forced to carry yellow ID cards that singled them out in public. They were forbidden from travelling and had their passports confiscated. They could no longer study certain subjects at universities, nor join social clubs or hold certain jobs. Telephones were confiscated and their movements monitored.

“They would accuse us of being the fifth column,” says Shuker. He didn’t even realize he had extended family until he left Iraq; speaking about relatives in Israel was dangerous. “Even mentioning Israel by name was forbidden.” Newspapers blanked out its name.

Then, in 1968, Saddam Hussein became vice president, and Jews were an even bigger target. On January 27, 1969, 14 Iraqis—10 of them Jewish—were publicly hanged in Baghdad’s Tahrir Square, a spectacle broadcast nationwide.

For the Shukers, the situation had become intolerable.

At 3pm on August 13, 1971, Shuker’s father gathered the family and told them they were leaving Iraq. They had just two hours to pack one small bag and nothing bearing their real names.

They left in the dark and were smuggled through the Kurdish mountains in the north. The family hid in a coffee shop basement until dark before continuing to Iran. From there, they flew to Britain and claimed asylum.

Though safe, life in England brought its own challenges.

“When I arrived, it seemed like it rained every single day for four or five months!” Shuker laughs. “We were used to sunshine. But here there was darkness. I was a fish out of water.”

Shuker’s ideas about England came from reading Dickens novels. “I thought everyone wore bowler hats and carried sticks. We thought they’d be big, tall people because they were rulers of the British Empire.”

He felt the country was “not welcoming to foreigners, probably nothing has changed,” he says, reflecting momentarily on current politics. His “Oriental looks” set him apart, as “they weren’t used to people of color.”

I ask Shuker if being a Jew made his integration in Britain more difficult. “Not really because at that point I had decided I didn’t want to be labeled as a Jew anymore,” he admits. “As a child, I used to cry silently and scrub my skin, asking God why he created me as a Jew if it was such a crime.”

Education helped him adapt. The British-style schooling he received in Iraq meant he knew enough English to pass his A-levels, before going on to study Mathematics at the University of Leeds, and later becoming a successful businessman.

Although Shuker had wrestled with his Jewish faith, he gradually re-embraced it before marrying Esther in 1987. They have three children and four grandchildren.

Esther’s family is Ashkenazi; he recalls how the British Jewish community felt alien when he first arrived, as most were of European descent.

In Baghdad, neighbors walked freely into one another’s homes. “Our doors were never locked. Here, in London, it took years before my mother even talked to the neighbors.”

His work in the community eventually led to his election as vice president of the European Jewish Congress, as well as vice president of the Board of Deputies of British Jews—the first Arabic speaker to hold the title.

Given his history, it is no surprise that Shuker is passionate about the rights of refugees and asylum seekers. His proudest achievement was his involvement in the Commission on Racial Inclusivity in the Jewish Community, a project about Jews of color, shaped directly by his experience as an outsider.

Despite building a family in London, Shuker never once forgot about Baghdad. In 2003, after the US-led invasion, Shuker did something he thought impossible—he went back to Iraq.

His father had recently died, never fulfilling his wish to return to his homeland to collect his law documents. As a lawyer, his father “never forgave himself for running away with forged papers.”

Shuker recalls feeling shaky when the taxi to the airport arrived, unsure whether he would even step onto the plane. But he did, and not only did he reconnect with his roots; he recovered his father’s documents.

Shuker’s story, and those of other Mizrahi Jews, is featured in Remember Baghdad, a 2017 documentary charting the 2,500-year presence of Jews in Iraq: a community that once made up a third of Baghdad and included parliamentarians, judges, scholars, musicians, socialites, and so on.

Shuker has returned several times, often at personal risk. In May 2022, the Iraqi parliament passed a law that makes it a crime to normalize ties with Israel. Violations can be punishable by death.

Yet Shuker remains undeterred. He is a big supporter of the Abraham Accords. Brokered by the US, the deal normalized relations between Israel, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Bahrain in September 2020, followed by agreements with Morocco and Sudan later that year. The deal has established full diplomatic ties and fostered economic, security, and cultural cooperation between countries that were once enemies. This year, Kazakhstan signed the Accords.

Although relations came under strain during the Israel-Gaza war after October 2023, Jews can wear their kippahs openly and even have a house of worship in Abu Dhabi.

“It’s a dream I never thought would happen in my lifetime,” Shuker smiles. “To be welcomed and celebrated in an Arab, Muslim country, not merely tolerated. It took me back to the first eight years of living in Iraq.”

He believes Jews and Muslims lived in relative peace for centuries, “but what changed was three things: Nazism, which was exported to the Arab world; Zionism and the creation of Israel; and Arab nationalism,” says Shuker. “I’ve always believed that pure antisemitism was a European evil. It was exported during the Nazi period. Yes, you’ll hear people saying Arabs treated Jews as Dhimmis who had to pay for protection, but I believe this is revisionist. Jews lived side by side with Arabs.” The Abraham Accords, he says, are a return to that state, and have “proved their resilience and permanency.”

Israel, says Shuker, can be the “Jewish quarter of a new Middle East.”

These days, Shuker’s base is largely in the UAE, as he feels “safer as a Jew in an Arab Muslim country than in Europe.”

Since the beginning of the war in Gaza, “anti-Israel sentiment has often spilled over into antisemitism,” says Shuker. Most recently, that has had murderous consequences—in Manchester, where worshippers were targeted outside a synagogue on Yom Kippur, and in Australia, where 15 people were murdered at a Chanukah party in Bondi Beach.

Rather than allowing such violence to deepen divisions, Shuker has dedicated his life to nurturing conversations that once seemed impossible.

“I’m a diaspora Jew, I’m culturally Arab. I feel I am the bridge between cultures,” he says.

As for Iraq, Shuker’s determined not to be “the last link in a chain of a hundred generations going back to 586 BCE,” when his ancestors were taken captive to Babylon by King Nebuchadnezzar. “I’m not going to let go of that history and legacy. Jews and Arabs were neighbors and partners; they were intimately connected. The Middle East was built on this,” he adds.

Like the painting of him praying at Ezekiel’s tomb in his London home, Shuker stands between worlds, determined that the link between Jews and Arabs will not fade on his watch.

Middle East Uncovered is powered by Ideas Beyond Borders. The views expressed in Middle East Uncovered are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Ideas Beyond Borders.

Wonderful article. I know Edwin, but didn't know that he had also read mathematics at university. I was also at Leeds University (another link), in my case a PGCE 1972-1973.

Powerful storytelling about a comunity that's been erased from the historical memory. The detail about Shuker scrubbing his skin as a child, asking why God made him Jewish, hit hard. What gets me is how he's turned that trauma into bridge-building work through the Abraham Accords. The fact that he feels safer in the UAE than Europe right now says alot about where antisemitism has migrated. I wonder how many stories like his exist from the mass exodus of Mizrahi Jews that never get told because the narrativ focuses elsewhere.