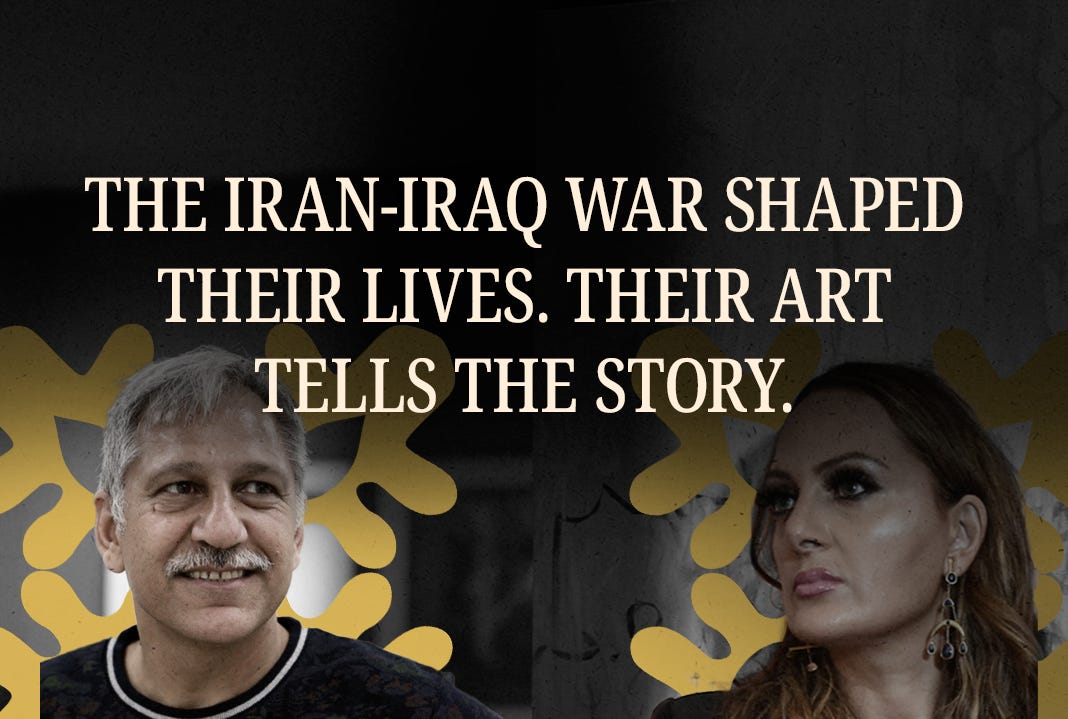

The Iran-Iraq War Shaped Their Lives. Their Art Tells the Story.

Keiany and Shamsavari grew up in the shadow of one of the 20th century’s deadliest wars, and its ghosts still shape their work. Their art captures what conflict destroys—and what creativity rebuilds.

For British-Iranian artists Dr. Mohsen Keiany and Sara Shamsavari, enduring a brutal war is not just a personal memory, but something that continues to shape their work.

The Iran-Iraq war (which lasted from September 1980 to August 1988) was one of the most destructive conflicts of the late 20th century. While the total number of casualties is unclear, it shaped Iranian identity and culture for generations.

Both Keiany and Shamsavari have transformed the pain from this trauma into something creative.

Keiany, a 55-year-old lecturer and artist who now lives in Birmingham with his wife and three children, remembers being a boy soldier, enlisted at 13 using his older brother’s birth certificate, abandoning a normal teenage life to face the brutal realities of war. Later, he would return to school as if the battlefield didn’t exist.

“The atmosphere, the propaganda—they wanted everyone to defend the homeland. To me, it’s a crime, children should study,” Mohsen tells me.

His brutal experience turned him against war completely. When he reads about any conflict, “I feel like I’m there, I feel what’s happening”.

Keiany’s 2019 collection Desensitised confronted Western audiences with the raw horrors of war, images some institutions deemed “too graphic.” Yet for Keiany, his art feels like a duty. “I wanted people to see the ugliness of war,” he tells me.

His work often draws on Persian mythology, updating the heroes of the Shahnameh (the epic of Persian kings) into contemporary contexts. His scrap-metal collection reflected the decline of certain bird species in the Middle East.

Shamsavari’s survival story, meanwhile, began in early childhood. Born during the Islamic Revolution to a mother who was Baháʼí (a persecuted minority in Iran), the family fled the country during the war. Sara, now 46, recalls hiding under a table with her brother as bombs fell, the lights hurriedly switched off to avoid detection.

As a child, she had kidney cancer, for which she was treated at London’s Great Ormond Street hospital. “It was my first time defeating death,” she smiles. “I’m here and still making art.”

Her identity was shaped by life as a refugee in South London, but her artwork is also seen as an indication of both trauma and renewal. “Refugees always carry that sense of trauma,” she says.

More recently, severe illness in 2023 took her “inward,” and she eschewed her usual photography for painting. Her exhibition “Where the soul finds its home” is currently displayed at the Persian-themed Kiani Tea House in central London. Each canvas contains fragments of Farsi text; the work features copper, gold leaf, salt, and lemon to evoke erosion and endurance, echoing the journey made by migrants.

The current discourse around immigration, she says, mirrors when her family first sought sanctuary in Britain. “There’s a lot of overt xenophobia and racism, and the targeting of minorities,” she says. “When refugees arrive in this country, they come to a hostile environment. It makes you feel that no one wants you.”

This summer, the British Embassy showed her work in Iran—a bittersweet feeling for Sara, as she was unable to visit. “It’s the first time any part of me has been back there. I’m dying to go to Iran and be with the people, because that’s what I care about.”

Both Keiany and Shamsavari were fortunate to have parents who nurtured their artistic instincts. Keiany recalls scratching drawings onto walls as a child, encouraged by his father, a carpenter who bought him coloured pencils. Though he briefly enrolled in a medical college, he abandoned it to pursue art in Esfahan, later becoming a lecturer in the UK.

Shamsavari’s mother and father, a psychologist and an economist, respectively, were equally supportive. “They weren’t stereotypically Middle Eastern,” she says. “They didn’t demand we become doctors or engineers. They allowed us to be free.” Her brother became an illustrator, and she herself studied at Central Saint Martins, a prestigious art and design college, launching a career that has taken her work across continents.

Shamsavari’s early photography often focused on immigrant communities, challenging stereotypes and encouraging empathy. One exhibition on women who choose to wear the headscarf sparked controversy, with fellow Iranians accusing her of promoting Islam and the hijab. For her, it was a nuanced exploration of choice and identity. “For people in Iran, it’s forced on them, it’s a form of trauma,” she explains. “I know some Iranians here who see the veil, and they will freak out. It’s wrong to tell women what to do with their bodies. We live in a polarized time; it’s awful and difficult. But with my work, I want people to see each other as human beings.”

Despite their different styles, both artists share the irony that their work has sometimes been less controversial in Iran than abroad.

One British institution told Keiany that some of his work might “anger the Muslim community,” he tells me. “I told them I’m showing you what’s happening in my region. I wanted people to see the ugliness of war.”

Keiany’s mythic references are often embraced as cultural heritage at home and even in Pakistan. While travelling in the South Asian country, he conducted research on nomadic tribes in Balochistan province, which led to the publication of his book, Balochistan: Architecture, Craft, and Religious Symbolism, in 2015.

Both artists remain deeply affected by ongoing turmoil. Keiany believes that migrants can still feel uprooted even when settled in another country. “Living here in the UK and my children being born here, sometimes I feel that displacement towards even myself,” he confesses. “I put myself in unwanted exile.”

Shamsavari speaks of the distress reignited by the 12-day war between Israel and Iran, which triggered her anxiety.

“The diaspora felt traumatized due to not knowing what’s going on inside Iran or how the people were,” she says.”

Keiany reflects on Woman, Life, Freedom—a protest movement in Iran that began in September 2022 following the death of Mahsa (Jina) Amini, who died after being arrested by the morality police for allegedly not wearing her hijab properly.

“I was here, and my people were dying in the street. It affected me so much,” says Mohsen.

His award-winning piece “The Motherland” is a haunting painting with blank shapes of military soldiers in the foreground, serving as a metaphor for the conflict in Iran. It was supposed to convey the idea that what’s happening in Iran is just temporary and can be fixed.

Mohsen admits that returning to Iran carries risk, and he has been investigated by the authorities on multiple occasions. “Any time I go there, I have a feeling I might be jailed,” he admits. And yet he perseveres because, “as an artist I’ve done my job in recording what’s happening in my time.”

Together, Dr. Mohsen Keiany and Sara Shamsavari show how the legacy of war and migration lives on for generations, shaping identities and creativity.

For both, art is not primarily a career but a way to document the realities the Iranian diaspora faces—and a means to prompt humanity to pay attention in moments when it is easy to look away.

Middle East Uncovered is powered by Ideas Beyond Borders. The views expressed in Middle East Uncovered are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Ideas Beyond Borders.