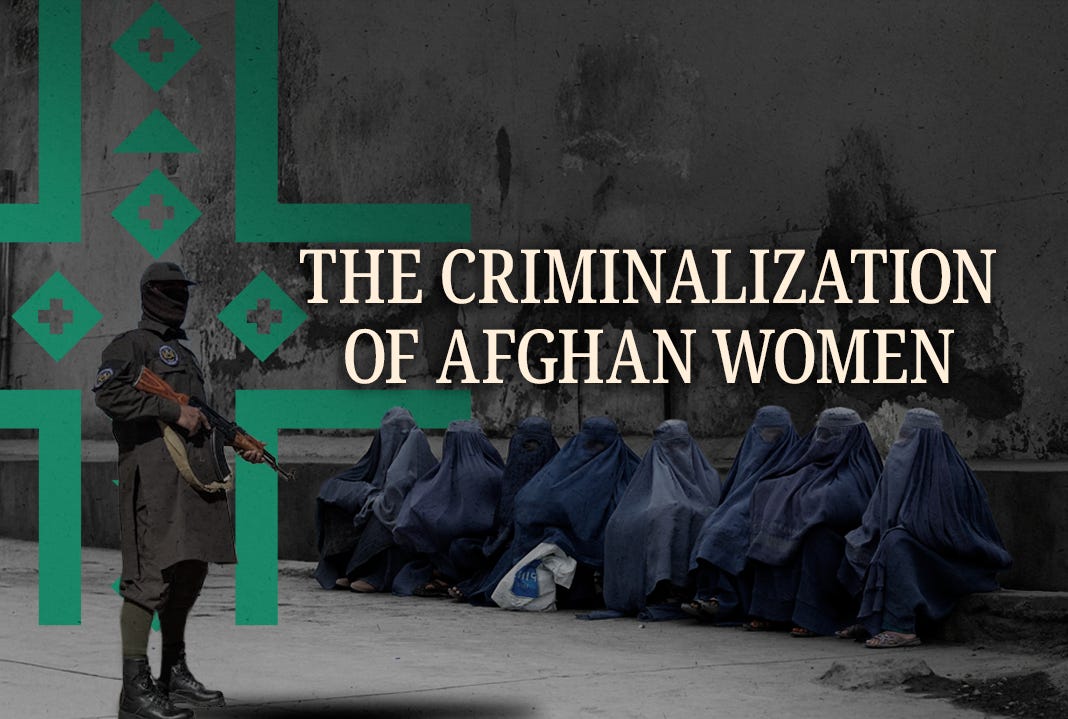

The Criminalization of Afghan Women

The Taliban’s new criminal procedure code embeds gender apartheid into Afghanistan’s justice system, strips women of legal protection, and demands an international response.

As Senior Director of Right to Learn Afghanistan, I have spoken with girls inside the country who instinctively lower their voices when they utter the word “future”—not out of shyness, but because they have learned that dreaming of one might draw attention they cannot afford.

With the introduction of the Taliban’s new Criminal Courts Procedure Code, even staying within the confines of the law offers no protection.

In early January 2026, the Taliban approved a criminal procedure law that formalizes what Afghan women have lived under since the regime’s return: a justice system where legal outcomes depend not on evidence or rights, but on status, gender, and conformity. The code assigns punishment by social class, denies defendants basic procedural safeguards, and grants judges sweeping discretion to criminalize ordinary behavior. It’s not a system meant to resolve crimes, but one designed to discipline a population—especially women—through the constant threat of arbitrary punishment.

Under Article 34 of the new code, a woman who repeatedly visits her father’s home instead of returning to her husband’s house can be charged with a crime. Even relatives who shelter her may face imprisonment. Article 32 states that a husband is only punishable for violence if a woman can prove severe, visible injury. If the bruises fade, the crime disappears with them. This means a woman must endure violence visibly to be believed. Women are legally being held captive in Afghanistan.

No longer protected as citizens, Afghan women are treated as property. They are legally subordinate to male authority, with their movement, choices, and safety controlled by husbands, fathers, and male guardians.

The code’s recognition of slavery makes explicit what its treatment of women implies: people can be owned. Article 4 states plainly that discretionary punishments “can be administered by a husband, or master (slave owner),” thereby acknowledging slave masters as legal authorities within the Taliban’s justice system.

This is in direct contravention of international law, which recognizes the prohibition of slavery as a peremptory norm from which no government may claim exemption.

The 1926 Slavery Convention, the 1956 UN Supplementary Convention, and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights all prohibit slavery in absolute terms.

Over the past four years, women in Afghanistan have been barred from education beyond elementary school, excluded from most forms of work, and prevented from moving freely without a male guardian. By embedding discrimination into judicial procedure—assigning punishment by status, denying basic legal protections, and empowering judges to police behavior rather than crimes—gender apartheid is codified into its jurisprudence. International legal experts warn that, taken together, these measures may rise to the level of crimes against humanity.

Not only does the new code codify gender discrimination, but it also dismantles the most basic principles of justice. There is no guaranteed right to legal counsel or the presumption of innocence. Confessions can be forced. Punishments vary not by the nature of the crime but by social status, while those in power are shielded from accountability.

For the first time in Afghanistan’s history, Article 9 of the Criminal Procedure Code of Courts formally divides society into a caste-like system of four unequal classes:

Religious scholars (ulama/mullahs)

Elite (tribal elders, influential commanders)

Middle class

Lower class

Punishment for the same offense differs by class, not by severity:

Clerics receive only advice, even for crimes.

Elites are summoned and advised.

Middle-class offenders face imprisonment.

Lower-class offenders face imprisonment and corporal punishment.

Now, legal impunity for Taliban officials makes it impossible for victims to seek justice when Taliban members commit crimes.

This code also violates children’s right to safety, exposing them to violence and a legal system that normalizes harm instead of protecting the most vulnerable. For children, this code means growing up in a system where violence is normalized, protection is absent, and fear replaces trust in justice. It teaches the next generation that power, not fairness, determines who is safe and who is punished.

One young woman told me, “Home is not safe, but outside is illegal.”

Every day that the world treats this as an “internal matter” is another day that Afghan women are told their suffering is tolerable. But no law that legitimizes violence is legitimate. No court that punishes victims is just. No regime that erases women deserves recognition.

The Taliban wants the world to accept this as normal governance. That expectation defies reason. What is being imposed is not a functioning legal system, but repression formalized through the courts.

While ordinary citizens, activists, and civil society around the world continue to stand with Afghan women, governments—especially those with real leverage—have largely stopped short of meaningful action. Expressions of concern are no longer enough. States must refuse to legitimize this legal abuse and take concrete steps to restore accountability. Without consequences, the Taliban has been free to expand and entrench what rights experts now describe as the world’s most misogynistic justice system.

What Afghan women are asking for is straightforward and urgent:

Formally recognize and codify gender apartheid as a crime under international law.

Pursue accountability for crimes against humanity, including legal action through international mechanisms.

Shut down Taliban diplomatic missions and deny them political legitimacy.

Freeze and sanction Taliban financial assets and funding channels.

Restrict Taliban leaders’ travel and movement through coordinated international measures.

End political negotiations that exclude women, and refuse engagement that treats their rights as negotiable.

Afghan women are not property, as the Taliban portrays them, nor are they just statistics, as the international community often counts them. They are students, mothers, daughters, teachers, poets, and leaders—and the would-be architects of a future that is being stolen from them.

The Criminal Courts Procedure Code leaves little ambiguity about how the Taliban intends to govern. It removes legal protection from women, restricts their ability to seek safety, and places judicial authority firmly in the hands of extremists insulated from accountability. The result is a court system that strips agency from the citizenry rather than adjudicating harm.

The question now is not whether the world understands what is happening, but whether it is willing to act on that understanding and decisively defend Afghanistan’s women—or leave them to languish under the Taliban’s barbarism while the rest of the world looks away.

Middle East Uncovered is powered by Ideas Beyond Borders. The views expressed in Middle East Uncovered are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Ideas Beyond Borders.