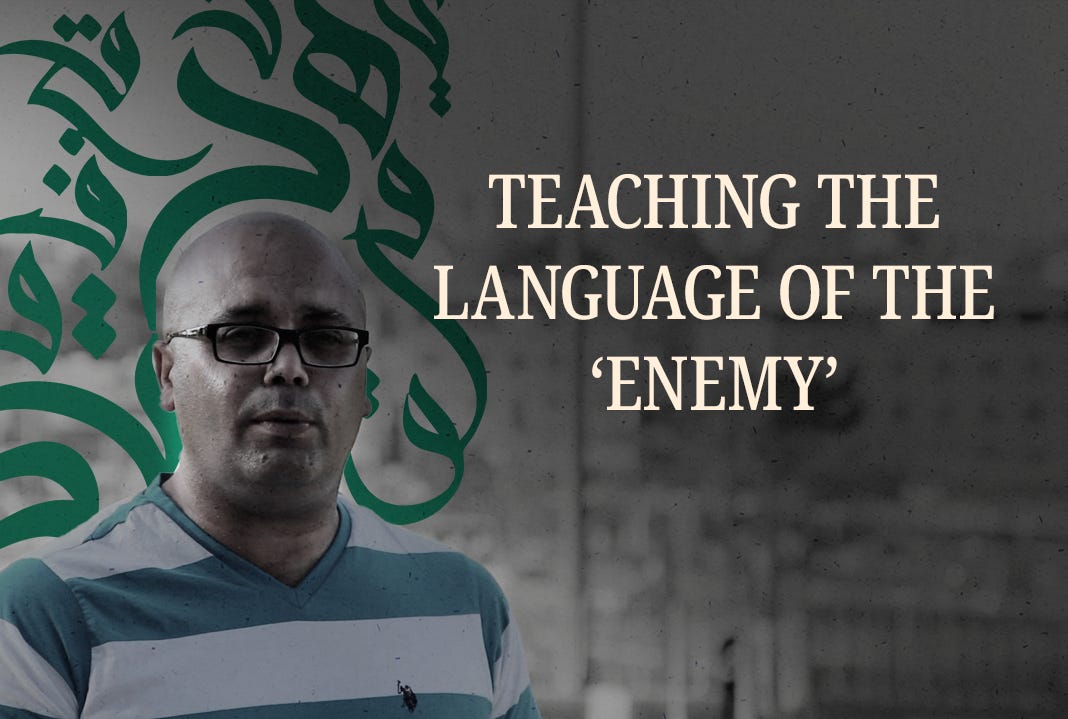

Teaching the Language of the ‘Enemy’

A Palestinian teacher challenges his Israeli students to see Arabic as more than the tongue of their adversaries.

In the nearly 30 years that Anwar Ben-Badis has been teaching Arabic, he has heard pretty much every reason why Jewish Israelis decide to learn his native tongue.

There are the liberal-lefties who want peace and coexistence. Retirees who believe it enhances brain cognition. And finally, the right-wingers who see it as the “language of the enemy”.

“This year, we had a lot of Israeli journalists joining the class. They said we want to understand Arab media and what they’re saying about Israel,” Ben-Badis tells me. “I say to them: before you try to understand Al Jazeera, why don’t you find out what the Palestinian in the street thinks and believes?”

It would be easier, he says, to describe himself as Arab. But he always introduces himself as Palestinian: “I tell them this is also my country. I’m bringing myself, my identity, and my knowledge.”

Opinionated and unapologetic about his identity, 48-year-old Ben-Badis does not mince his words over our Zoom interview. The son of a Christian mother who married his communist Berber father, he personifies the kind of complexity that defies easy labels in a region where things are rarely straightforward.

Other students of Ben-Badis’s are Israeli doctors who work with Palestinian staff.

“Two months ago, I had surgery, and in a team of eight Arab doctors, one was Jewish,” Ben-Badis says. “She joined my class because she wanted to understand her colleagues.”

In the last few years, settlers living in the occupied West Bank have enrolled in his classes. “It’s challenging for me as a teacher because some of these people can be very arrogant.”

Although 20-25 percent of Israel’s population is Arab, only around 5-6 percent of Israeli Jews can speak Arabic, despite Hebrew and Arabic being part of the same language family.

A poll in September revealed that many Jewish parents, especially religious and Haredi ones, didn’t want their children to learn Arabic or be taught by Arab teachers in schools—signalling a potential worsening in the already-strained Jewish-Arab relations in Israel.

Still, there’s a growing realization across political lines that Arabic is vital, whether for understanding neighbors or perceived adversaries.

Even Oren Hazan, a right-wing parliamentarian who lives in the illegal settlement of Ariel in the occupied West Bank and once harassed Palestinian families, introduced legislation to make Arabic mandatory. Alas, it didn’t pass the Knesset.

Arabic was once an official language in Israel, but it was downgraded to “special” status under the controversial 2018 Nation-State Law.

While the aftermath of the October 7 attacks led to renewed tensions between Israelis and Palestinians, it ironically also led to a surge in Arabic learning.

The online school Madrasa (which means ‘school’ in Arabic) has over 150,000 Israelis enrolled in Arabic courses.

Following the intelligence failure on that day, the Israeli Defence Forces have made it mandatory for all soldiers and officers in the intelligence wing to train in Arabic language and Islamic Studies.

But some believe this militarized way of teaching will further alienate Jewish-Israeli students from Arabs, rather than serving as a potential bridge between them. “They’ve grown up knowing it as the language of the ‘enemy’,” Ben-Badis explains. Arabic is not compulsory in Israeli schools. While it can be taken as an elective, in practice, very few schools offer the course. In the 2021-2022 school year, for example, only 11,000 Hebrew-language high school students studied Arabic, out of a 253,000-strong student body.

“They should have kept Arabic mandatory in school,” says Ben-Badis.

Teaching often focuses on Modern Standard Arabic (Fusha) rather than the spoken dialects used daily.

Very few Arabic teachers in Jewish schools are Arab, which means the language is often taught without cultural or conversational context. They tend to be Israelis who have worked in the secret service and are fluent in Arabic. But Yaron Sivan believes employing native speakers gives students a greater understanding of Arabic culture.

“Teachers bring themselves to class, their stories, their childhood, you can feel the difference when you learn from them,” he says.

Sivan manages Ha-ambatia, or “The Bathtub”, a private language school with branches in Tel Aviv and Haifa. It was initially set up by Ariel Olmert, the son of former prime minister Ehud Olmert, who added Arabic classes to its French offerings over a decade ago.

Learning the language post-October 7 has become a “stance”, says Sivan, “especially when the political sphere is dominated by fascist idiots—excuse my French!” For such people, studying Arabic is a part of activism, he says, adding: “It’s showing acceptance.”

After the Hamas attack, a lot of students who had enrolled in Ben-Badis’s class at the Jerusalem Intercultural Center dropped out; only a portion eventually returned. This year they have 200 students. But it hasn’t been smooth sailing.

“Some students demanded I condemn what happened on October 7. I refused,” Ben-Badis frowns. “I said you’re not going to test my humanity like this. Asking me this means you doubt I’m even a human being. Some of them respected me more. Some left class. It was a tough time.”

Ben-Badis admits discussing politics in lessons has become “too dangerous”. A student recently complained about him for criticizing the military.

He is also worried about the rise in students bringing weapons to class. Before October 7, he could have told them to leave, something he can’t do now.

As any teacher would tell you, one must know how to assert authority over the class, or there will be chaos. “I behave like I am the king, otherwise the students would eat me up!” he smiles.

At the Jerusalem Intercultural Center, where Ben-Badis teaches, class meets once a week for three hours. Students are not allowed to speak in any language except Arabic, even during their break. He makes them complete an exercise every day, which they have to send back to him to mark.

When I tell Ben-Badis that I’m also learning Arabic, he even sends me homework!

Part of language learning involves meeting and conversing with native speakers. For that reason, the institute also hosts language exchange sessions between Palestinian and Israeli students. Ben-Badis also takes Israelis on tours in the eastern part of Jerusalem to meet with Arab business owners and shopkeepers. As they live in the western part of the city, for many of them, this will be their first interaction with a Palestinian.

As well as understanding their fellow Arab citizens, Israeli Jews also want to connect with their own heritage. The Mizrahis are usually third-generation Israelis who wish to speak the language of their grandparents who fled North Africa or the Middle East.

“There’s been a boom in Mizarahi culture in recent years, particularly in music,” says Rabbi Elhanan Miller. “That self-confidence has normalized Arabic for Jews.” Miller began studying Arabic at the age of 13. Now fluent, he is a regular on Arabic television channels.

He is also the founding editor of People of the Book, an online initiative that teaches Jewish faith, culture, and history to Muslim audiences. The YouTube and Facebook pages now boast over 200,000 subscribers and millions of annual video views across the Arab world, indicating a mutual desire to understand the other.

What happens in class, however, doesn’t stay in class. One example Ben-Badis gives me is how he stopped Israelis from using a foul Arabic word (it must be really bad, because Ben-Badis refuses to tell me what it is). His own mother would kill him if he dared to utter it in front of her, he says.

“I had one broadcast journalist who said on her show to another guest that she wasn’t going to use that word anymore, ‘because my Arabic teacher said I shouldn’t. ’ She said it live on air as well!” he smiles.

Because for Ben-Badis, teaching Arabic is his way of spreading positivity about his people and culture. “I get them to think of Arabic in a beautiful way. This is my act of resistance.”

Plenty of headlines have been written in the past about Israeli Jews learning Arabic. Is this yet another trend?

Yaron Sivan believes it will “either stay at this level or grow even more. There’s a cultural change in Israel. People feel like they need to learn Arabic for good reasons.”

Arabic lessons in Israel may or may not solve decades of mistrust and division, but they’re indeed reshaping the conversation. What was once viewed as the “language of the enemy” is slowly being heard as the language of neighbors—and perhaps, one day, of equals.

Middle East Uncovered is powered by Ideas Beyond Borders. The views expressed in Middle East Uncovered are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Ideas Beyond Borders.

UNRWA: The Factory of Eternal Conflict

https://open.substack.com/pub/sergemil/p/unrwa-the-factory-of-eternal-conflict