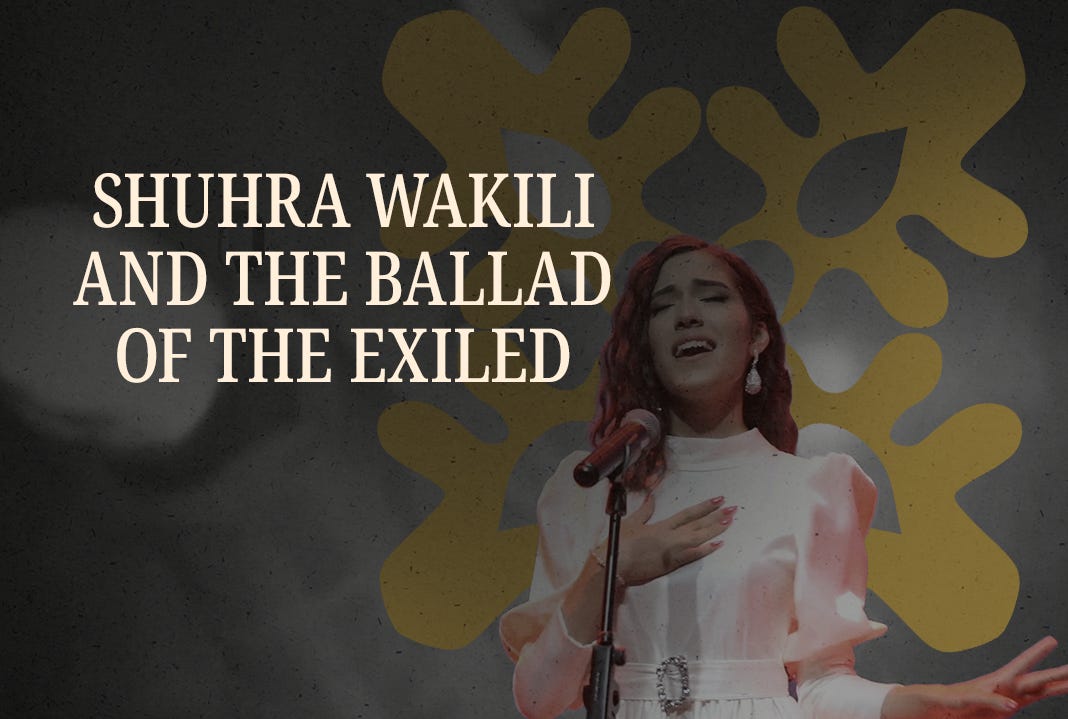

Shuhra Wakili and the Ballad of the Exiled

Her journey from Badakhshan to Florida carries the voice of a nation that cannot sing for itself.

When Shuhra Wakili first stepped onto a stage as a teenager in Tajikistan, she couldn’t bring herself to look at the audience. Her eyes were fixed on her shoes as she sang a tribute to mothers. When she finished, the packed hall erupted into applause and cheers. Her mother, who was in the audience, was in tears.

At that moment, Wakili recalls, she understood the power of her voice. “I saw people stand, clap, and cry,” she said. “That’s when I gained confidence and realized music was something I wanted to pursue.”

Now 21, Wakili has performed across many cultural events, recorded songs with Afghan producers, and begun to build a music career in exile. But her rise as an artist comes against the backdrop of Afghanistan’s collapse into silence, where the Taliban’s return to power has erased public music from the country entirely.

Born in Badakhshan in 2004, Wakili fled with her family to Tajikistan at age 11. At first, she struggled with loneliness, missing her home in Faizabad, where she had her earliest memories. Over time, she came to view Tajikistan as an extension of Afghanistan, rather than a place of exile. “Without borders, both countries are the same,” she said. “We share culture and language. I never felt like a refugee there, something which I realized later.”

Wakili graduated from an Afghan-based school in Tajikistan. During her final year, she applied and was accepted to the United World Colleges (UWC), a path that later led her to the Netherlands. In 2023, she was finally able to sort her paperwork and leave everything behind in Tajikistan to embark on yet another adventure. Stepping away from her family for the first time was challenging, but it was essential for her. UWC helped her on her path towards emotional and personal independence. After graduating from UWC, Wakili secured a scholarship at Tampa University in Florida to begin her undergraduate studies in the fall of 2025.

Wakili grew up in a family where music was always present, even if no one in the family pursued it professionally. Instruments like the harmonium, tabla, and guitar filled their home. “Someone was always playing something,” she recalled.

Her first stage performance came at an Afghan embassy event in Tajikistan on March 8, International Women’s Day. The first year she asked to sing, her teacher said no. The following year, she insisted. Her performance moved the teacher to tears and gave Wakili her first taste of what it meant to be heard.

By the time she graduated high school, she was performing regularly at embassies and cultural events. In 2021, she signed with Qiam Production, where she recorded several songs that were warmly welcomed by the people and her ever-growing fan base on social media. “They supported me a lot,” Wakili said. “The feedback was all positive.”

Music is the thread Wakili clings to, the thing that carries her through tough times. “It’s a way of expressing emotions—anger, sorrow, happiness,” she said. “For Afghan women, music can be a voice and medium.”

But voices like hers have been gagged inside Afghanistan. Since August 2021, the Taliban have banned most forms of public music. Musicians have fled, gone into hiding, or been forced to destroy their instruments. Concerts and festivals that transcended a single industry have now come to an end. Even women’s voices have been pushed off the airwaves: Radio stations run by or featuring women have been shuttered for playing music or broadcasting female voices. Countless jobs were lost as whole industries became illegal overnight.

From day one, the Taliban made it clear that music and art have no place in their regime. The ban on music initially came into effect at wedding ceremonies, public spaces, taxis, and later even at people’s private residences. Once a booming industry in Afghanistan, musicians closed their shops, and those who were able salvaged what they could to protect their instruments from destruction.

The suppression comes after two decades in which music had re-emerged as a valued art form. Yet Wakili is critical of how it developed: “People came to see it more as an industry than an art. Musicians could make money, but music itself lost its cultural and artistic value.” Wakili acknowledges that many trailblazers have paved the way for her and others to follow; however, the music industry in Afghanistan has had a dark shadow following it for a long time. Its survival was never guaranteed.

The stakes are high. Afghanistan once hosted institutions like the Afghanistan National Institute of Music and the Zohra Orchestra—the country’s first all-female ensemble—whose members all scattered in exile. Today, Afghanistan ranks 175 out of 180 in the global press freedom index, and cultural expression is among the first casualties. The Taliban’s recent internet crackdown signals there are even darker times ahead.

Wakili is keenly aware of the gap between her opportunities abroad and the suffocating conditions for young artists at home. “Young people in Afghanistan have so much energy and potential, but their hands are tied,” she said. “Those of us in the diaspora carry a heavier burden. We must build ourselves first, and then help others.”

Her own mission, she says, is to use her platform as a singer to amplify the voices of Afghan women. “It may not change everything, but at least this is what I can do. Even small contributions matter.”

As Wakili studies in Florida, she continues to write, sing, and perform. But her ambitions remain tethered to Afghanistan and her people. Her path from Badakhshan to Tajikistan, the Netherlands, and finally America illustrates the determination and promise of Afghan women.

“Music is more than business,” she said. “It’s art, it’s culture, it’s resistance. And even if Afghanistan has been silenced, we have to keep singing.”

Middle East Uncovered is powered by Ideas Beyond Borders. The views expressed in Middle East Uncovered are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Ideas Beyond Borders.

I knew this, and I didn't know this. That is, it was only vaguely in my mind. Thank you for bringing focus to the music situation in Afghanistan, and more power to Shuhra Wakili and all other musical artists who are carrying on in whatever ways they can. Music is a gift of God.

No music, unimaginable. "Oh the horror" of darkness. The Prince of Darkness truly reins in Afghanistan