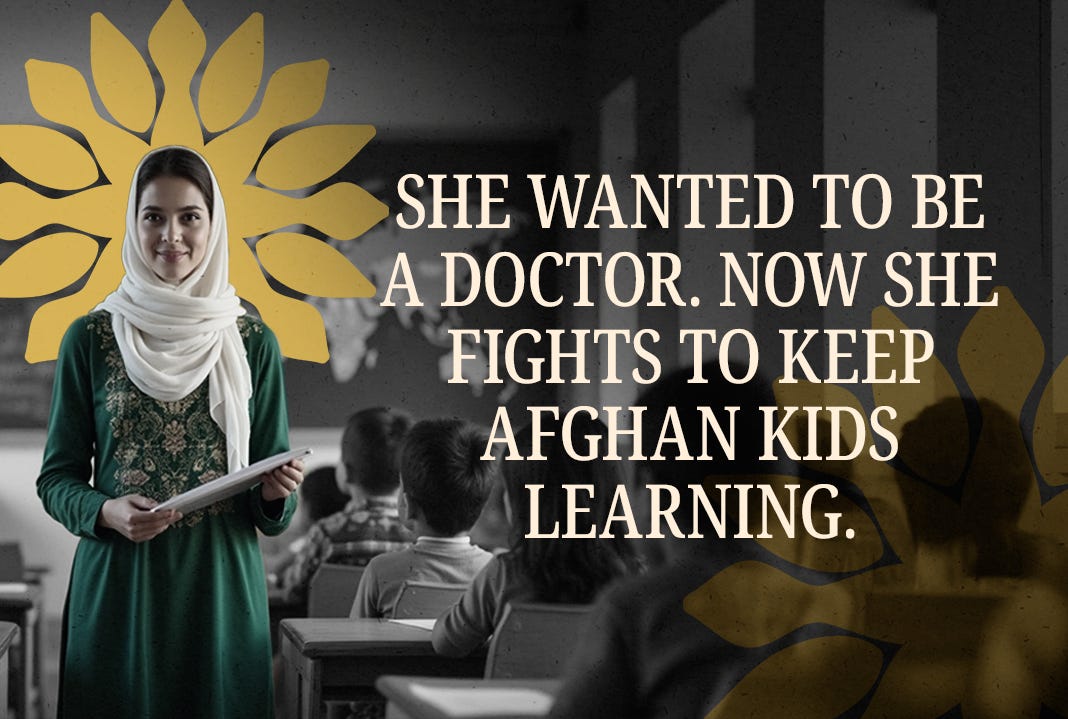

She Wanted to Be a Doctor. Now She Fights to Keep Afghan Kids Learning.

With her dream of medicine denied, Rohila now stands at the front of a classroom, determined to keep education alive for Afghan children.

Middle East Uncovered uses pseudonyms to protect our sources in Afghanistan.

Kandahar, Afghanistan – At just 21, Rohila never imagined she would become a teacher. Her dream was to study medicine. Instead, she now stands before classrooms of Afghan children, trying to keep their curiosity alive in a country where education has been gutted and teachers are disappearing.

“Why shouldn’t learning be fun?” she says of her philosophy. She builds lessons around games, cartoons, and what children see online. “These kids are sensitive. You have to meet them where they are.”

Yet even the most committed teachers cannot escape the reality of Taliban rule. Schools are under constant scrutiny. Curricula are stripped of subjects deemed “un-Islamic.” And qualified teaching staff, particularly women, are being forced out. The handful of female teachers who remain are teaching at private or public schools, typically up to the sixth grade. And to make matters worse, the Taliban recently shut down the internet for the entire country, plunging millions of already desperate people into darkness and isolation. Although the internet was restored 48 hours after its shutdown on Monday, the threat of future closures still exists.

Rohila was once a star student herself. Raised in Kandahar, she excelled at one of the city’s top public schools, competing in spelling bees, story-writing contests, and youth science programs. “I was always the youngest student they would send to competitions,” she recalled.

Her education was important to her family. Before entering school, she learned English from her grandfather, a retired teacher who once studied at New York University. Later, a neighbor prepared her for classes where her grandfather couldn’t, such as science and math.

By 2021, she was on track to graduate and pursue a career in medicine at a University in Kandahar. But the Taliban’s return closed that door. The Taliban banned universities for women, and her studies ended. “The longer I stay here, the more I waste my time not studying,” she said.

Rohila’s personal loss reflects a broader crisis. According to UNESCO and Human Rights Watch, 2.2 million Afghan girls are banned from secondary schools, which represents 80% of Afghan girls of school age. Over 100,000 women have been expelled from universities since 2021. In Kandahar, teachers are ordered to expel girls over age 12, fire Shia staff, and enforce burka dress codes.

The situation for teachers is just as dire. Women who remain in classrooms face harassment and restrictions, including bans on owning smartphones. Salaries have plummeted, thousands of schools have closed, and international aid to support teachers has dwindled. Rohila recalls multiple instances where Taliban members intimidated teachers from her school into wearing Burkas and warned them not to teach banned subjects.

Without qualified staff, the quality of education has collapsed. In many villages, Taliban loyalists with no formal training are appointed as teachers. Others use classrooms as pulpits for indoctrination. Very few female teachers remain employed today. The most recent data from 2020 showed that over 200,000 teachers were employed in Afghanistan, with 80,000 of them being women. Although exact numbers are not available at this time, it is estimated that the majority of those female teachers have lost their jobs.

Rohila witnessed this firsthand when a young student told her he wanted to “become a Taliban” because “they have cars, money, big houses, and guns.” She remembers the heartbreak: “These are just children. They don’t know what has been done to have that lifestyle.”

Kandahar, once considered more liberal than outsiders might expect, had a thriving educational scene for women just a few years ago. “There were courses in graphic design, coding, even nursing and pharmacy,” Rohila recalled. “Girls were studying skills that gave them futures.” Now serving as Taliban supreme leader Hibatullah Akhundzada’s base of command and control, Kandahar is the center of political power of the terror group. Every decree and regulation is heavily enforced.

Teachers, meanwhile, operate under threats. “The Taliban came to our school,” Rohila recounted. “They told us: expel girls above 12, fire Shia staff, or we will shut you down.”

Teaching was never Rohila’s ambition. Yet with universities closed, it became her only option. She tries to bring creativity into her lessons despite the danger. “It wasn’t my plan, but I try to be honest in my job,” she said. She places a strong emphasis on her students thinking for themselves rather than following the narratives of the Taliban. Her teaching methods are stealthily centered around advocacy for human rights, women’s rights, and the importance of science and education.

She embodies the countless Afghan women who have become educators out of necessity, keeping classrooms alive with little support and often in defiance of Taliban orders. Networks of underground and above-ground schools are working tirelessly to confront the Taliban’s agenda of indoctrination. However, without systemic change, a generation of Afghan children will grow up without proper teachers or access to real education.

Rohila’s dreams of leaving Afghanistan to study abroad. She has applied for scholarships, but with international exams like TOEFL and IELTS banned, her documentation is incomplete. “I want to pursue the field I love most,” she said. “But here, I cannot.”

Afghanistan is not only losing its students, but also its teachers. Teachers who are trusted with the future of a generation that is slowly being lured away from critical thinking, enlightenment, and liberalism as they try to survive living under this regime.

“Afghanistan’s children are being robbed of their future,” she said quietly. “We try to teach, but with no real teachers left, who will carry us forward?”

Middle East Uncovered is powered by Ideas Beyond Borders. The views expressed in Middle East Uncovered are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Ideas Beyond Borders.