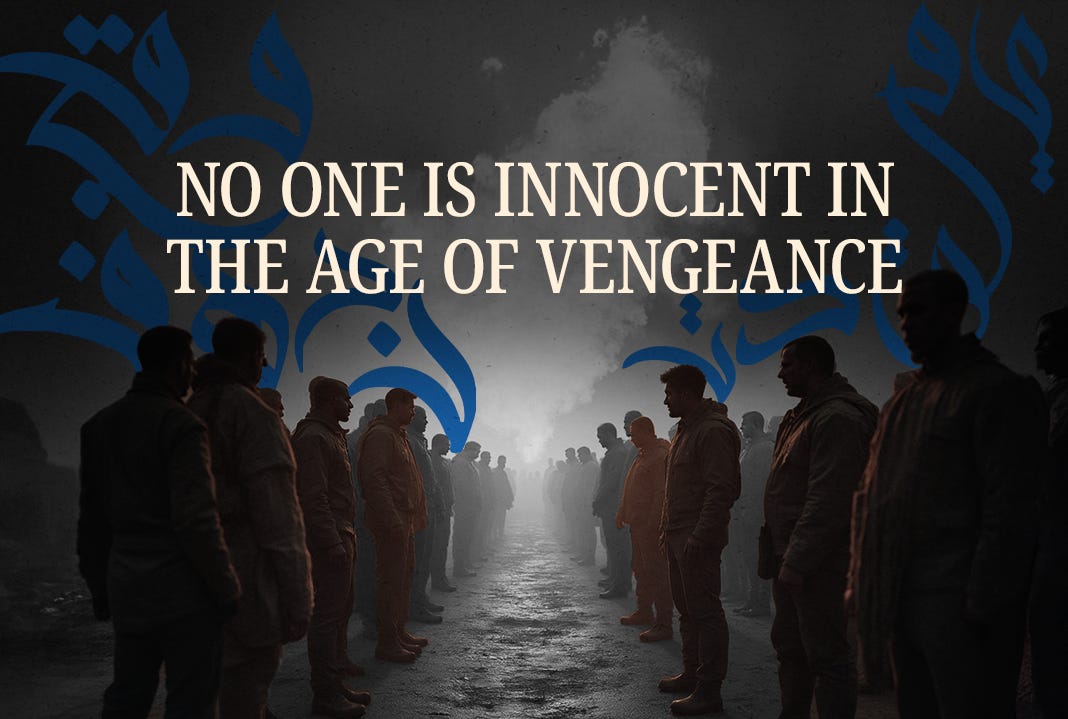

No One is Innocent in the Age of Vengeance

Justice without forgiveness is just revenge by another name. Breaking the cycle of oppression lies in building a future where even our enemies are safe

When people rise against injustice, what are they truly seeking? Is it the establishment of a just order, or simply a reversal of roles, where yesterday’s victims become today’s masters of the very system they once despised? History, with its unflinching clarity, suggests the latter. Most revolutions do not dismantle oppressive structures; they merely invert them. The cycle of domination grinds on with new actors at the helm.

The more brutal the regime being challenged and the bloodier the showdown, the greater the likelihood that this tragic pattern holds. Victory, in such cases, does not mean justice—it means revenge. The tables turn, the seats are switched, but the old logic of power remains.

Those who preside over unjust systems understand this all too well. They know what awaits them if the revolution triumphs: not reconciliation, but retribution. This knowledge shapes every decision they make when rebellion comes. In Syria, the ruling clique knew precisely what they had built—a system that could only breed vengeance. That is why they fought with such ferocity, why they unleashed unimaginable brutality. And that is why, even after their defeat, the promise of freedom did not automatically follow.

Because here is the truth no one wants to utter: we are all sectarians, and we are all complicit. We are not just victims of a despotic culture; we are also its custodians. Its architects may be long gone, but their disciples walk among us, their authority unchallenged. We cry foul when wronged, but we embrace the same ethos when given the chance to rule. The oppression we abhor in others we rationalize in ourselves.

The Assads did not invent sectarianism, but they did perfect the art of manipulating it. Sectarianism is our inheritance, the unspoken script that governs our politics, our loyalties, and our fears. We have yet to grasp what citizenship truly means—a condition that transcends tribe, creed, and confession. Until we do, the cycle of domination and reprisal will remain unbroken.

In Islamic law, a dhimmi (ذِمِّيّ) refers to a non-Muslim living under the protection of an Islamic state in exchange for paying a special tax called the jizya. Dhimmis are granted certain rights, including the protection of their life, property, and religious freedom, but are also subject to certain restrictions and obligations. In today’s Syria, and elsewhere in the region, we are all, in a sense, dhimmis; we are all practitioners of dhimmitude.

This is no longer about a particular religion, but about a mindset deeply ingrained in all of us, irrespective of our faiths—a willingness to accept hierarchy when it favors us and to rebel only when it doesn’t. Some commit injustice under the guise of preemption. Others justify it as payback for past humiliation. Who cast the first stone? The question is irrelevant now. What matters is that we are all hurling stones still. When it comes to this kind of affliction, we are all patient zero.

Breaking this cycle is the responsibility of those who hold power today. But here lies their dilemma: how can they dismantle the machinery of oppression today without paving the way for their own subjugation tomorrow? Indeed, how do we build, in a climate of mutual distrust and antagonism, a system that guarantees rights not only for ourselves but for our perceived rivals and detractors—and for generations to come?

If the answers were easy, something we could stumble upon as we wade through the mire of blood, hate, and sacrifice, we wouldn’t be where we are today. The answers demand deep and painful soul-searching and an ability to envision a future for all, not just for our “tribe.” They require empathy for those who wronged us, and the courage to let go of things we hold sacred. Because nothing should be more sacred than life—our lives and those of our perceived enemies.

Yes, there are still times when self-sacrifice is necessary, but these times should be the exception, not the norm. People should make those choices with their eyes wide open, fully understanding what they are fighting for and why their sacrifice matters for the desired outcome. Most of what is happening in Syria today is suicide disguised as self-sacrifice, acts of despair camouflaged as martyrdom—a cynical deployment of the sacred in service of profane impulses, ambitions, and the interests of corrupt elites playing war games.

The most essential virtue for breaking this cycle is forgiveness. Often maligned and mistaken for weakness, forgiveness requires more strength and bravery than most can muster. But the key to a new beginning and a better future lies in our ability to summon it.

If morality were easy, we would all be saints. But morality is hard, and justice harder still. And yet, until we accept our collective guilt and abandon the zero-sum logic of sectarian survival, there can be no real future—only the endless repetition of a bloody past.

Middle East Uncovered is powered by Ideas Beyond Borders. The views expressed in Middle East Uncovered are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Ideas Beyond Borders.

Well said, sir. The parties to the many conflicts in the region fundamentally do not want peace; they want to win. And a basic premise regarding human nature is that revenge is normal. Hence the call for submission to a transcendent authority. Unfortunately, the sacred depends upon the profane for all of its manifestations.

You say that forgiveness is maligned & misunderstood as weakness. In the Islamic mind, does that also mean shame/disgrace? In what circumstances, if any, is forgiveness seen as a positive thing in Islam?

How can that mindset be changed apart from Christianity in which forgiveness is both one of the greatest virtues and a requirement?