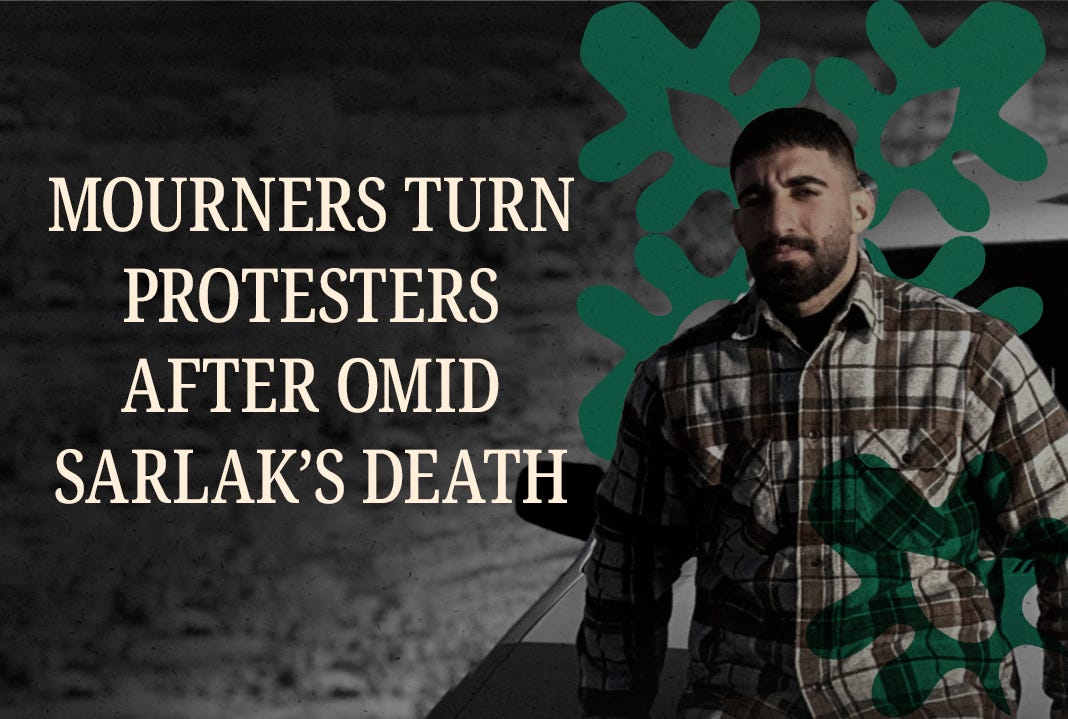

Mourners Turn Protesters After Omid Sarlak’s Death

After burning a portrait of Iran’s Supreme Leader, he was found dead in his car with a gunshot wound to the head. His death has turned him into a new symbol of opposition to the Islamic Republic.

In the western Iranian town of Aligudarz, funerals are usually solemn, uneventful affairs. But as grief-ridden mourners clad in black gathered round the coffin of 22-year-old Omid Sarlak—crying and beating their chests—chants of “Death to Khamenei” began sweeping through the crowd. The burial had become an impromptu protest.

“We will kill whoever killed my brother,” some of them cried out, while others described Omid as a “flower that has withered.”

Sarlak, an athlete in his 20s, was found dead in his car with a gunshot wound to his head on November 1, days after filming himself burning the portrait of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei. There were traces of gunpowder on his hands. Iranian police said Sarlak had died by suicide. But his family and activists rejected the police’s account of suicide, and at the graveside, the anger that had simmered online spilled visibly into the public space.

Since that day, Sarlak has become an icon, and his death has inspired others to burn photos of Khamenei in solidarity—an act that carries severe consequences under Iranian law.

Suspicions grew after a widely circulated video showed Sarlak’s father reportedly saying at the site of his son’s death: “They killed my champion here.” Later, in a televised interview aired by state media, Sarlak’s father urged people to “not pay attention to what’s circulating on social media and to let the judicial authorities handle the matter.” Activists called the video forced and said the family was under surveillance.

For those who knew Sarlak, the official explanation of his death never made sense. In a final act of defiance, Sarlak had posted videos on Instagram showing a burning photo of Khamenei with the voice of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (the Shah who was overthrown in 1979) playing over it.

In another story tagged #DeathtoKhamenei Sarlak wrote: “How long should we endure humiliation, poverty, and being ridden over? This is the moment to show yourself, young people. These clerics are nothing but a stream for Iran’s youth to cross.”

A week before he died, Sarlak contacted one of his idols, the Iranian wrestling champion Ebrahim Eshaghi.

“Omid was a brave, kind-hearted boy, fond of laughing and full of a zest for life,” Eshaghi tells me. “He messaged my Instagram page one week before he was killed and said [the authorities] were following him and that if anything happened to him, I should be his voice. In my opinion, this is definitely a state murder.”

Sarlak’s death reignited some of the anguish that emerged after the death of Mahsa Jina Amini, a Kurdish woman who was killed while in police custody after being arrested for wearing “improper hijab”. Her death, in 2022, ignited nationwide protests.

Dissident actor Hamid Farrokhnejad, who has long been a vocal critic of the regime, has dedicated his social media to sharing videos of protesters. He told Middle East Uncovered:

“Ali Khamenei is not the leader of a government but the head of a terrorist cartel known as the Islamic Republic, which has taken Iran hostage and for decades has actively promoted terrorism throughout the region and the world. We, the people of Iran, will repeat his act in remembrance of Omid Sarlak so that his sacrifice is never forgotten.”

Eshaghi has been a fierce opponent of the Islamic Republic since the killing of fellow wrestling champions, Navid Afkari and Amin Bazargar.

Afkari was accused of murder (something his friends and family denied) and imprisoned, where he was tortured for two years before being executed in 2020. Bazargar went missing shortly after protesting Navid’s death. His remains were later discovered on a mountain in Shiraz province.

When Eshaghi spoke out about this, he was detained by the intelligence services for a week. After they threatened his family, Eshaghi left Iran for Germany.

“The people of Iran are disgusted with the Islamic Republic regime and they want this criminal regime to be destroyed as quickly as possible,” he tells me. “The regime, until now, has only been able to stay standing by killing its own people.”

This, however, is just one rupture in the Iranian regime’s authority. Just recently, a video was circulated online showing two soldiers openly waving the pre-revolution flag at a Metro station.

The pair, dressed in army air defence uniforms, unfurled the tricolored banner emblazoned with the lion-and-sun emblem, a potent symbol of the ousted Pahlavi monarchy, on a crowded platform. They were subsequently arrested.

The pre-revolution flag, banned under the Islamic Republic, has surged in visibility during nationwide unrest.

The regime has been under pressure following the country’s worst water crisis in decades, which has depleted reservoirs and left taps running dry, including in parts of the capital, Tehran. Authorities were previously warning they would have to evacuate the city of 10 million people.

But then on Monday, rainfall caused floods in parts of western Iran. Footage published from Abdanan, in Ilam province, showed torrents of water sweeping through residential districts and damaging roads and neighborhoods.

Until that point, there was speculation (and perhaps hopes) from some quarters that the water mismanagement, along with dissatisfaction with the government, could topple Iran’s leadership.

According to Behnam Ben Taleblou, senior director of the Iran program at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD) in Washington, DC, the government is easing internal repression, such as tolerating symbolic protests or loosening hijab enforcement in some places, because it cannot simultaneously face the risk of another war with Israel and suppress domestic dissent.

“Polling shows that around 80-85% of people are strongly anti-regime. The regime knows that it long ago lost the social legitimacy argument. Its strategy, in the face of this loss, is to render the population afraid or apathetic,” he says.

This is why, for example, the regime is allowing concerts (usually heavily restricted) or recently erected the statue of the ancient Persian king Shapur in Tehran’s Enghelab Square. The Islamic Republic is making tactical choices, not ideological shifts.

“It buys them time,” says Ben Taleblou. “These guys are tacticians; they’re in the business of preserving, protecting, and defending their government as best as possible. That’s how they plan to survive the next round.”

In the meantime, the people of Iran continue to defy their regime—despite the consequences. When asked if he is scared, Ebrahim Eshaghi simply replies: “I am the voice of my friends and the voice of the oppressed people of Iran, and I try at every moment to do something so that we weaken the regime more and more. And I have no fear—neither of death nor of the Islamic Republic.”

Middle East Uncovered is powered by Ideas Beyond Borders. The views expressed in Middle East Uncovered are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Ideas Beyond Borders.

The transformation of Omids funeral into a protest shows how deepl the frustration runs in Iran. When someone like Eshaghi says he has no fear of death, it really captures the stakes. These acts of defiance carry immense personal risk, but they keep hapening despite the consequences. Its striking how the regime seems to be making tactical shifts, like allowng concerts or loosening hijab enforcement, just to buy time.

Repression always leads to instability. The best thing the Iranian government can do is create a real democracy that gives its people the freedom to express themselves. That way Iran’s leaders and people can work together to fight the Zionists and imperialists who keep attacking them.

Also, on an unrelated note - the FDD cited in this piece is a known Zionist front with an agenda and therefore a horrible source to cite. Just a thought…

https://open.substack.com/pub/mirrorsfortheprince/p/israels-attack-on-iran-highlights?r=v623r&utm_medium=ios