Is It Time to Stop Punishing Syria’s People for Assad’s Crimes?

The story of Syria’s decline is about more than Assad—it’s about the tools the world used to stop him. Trump’s call to lift sanctions could unlock aid and investment, or entrench a new autocracy.

Earlier this week, President Donald Trump made a stunning announcement during a visit to Saudi Arabia: he would order the cessation of U.S. sanctions on Syria. “We’re giving Syria a chance at greatness,” he declared. But is it a wise move?

After 14 years of brutal civil war, Syria is a shattered state. Over 90% of its population now lives below the poverty line. Schools, hospitals, and water systems lie in ruins. Blackouts are routine. Supermarkets are either empty or filled with goods priced beyond reach. For many Syrians, basic rights—electricity, clean water, education—have become unattainable luxuries.

And while Western sanctions were imposed to punish Bashar al-Assad and his regime, they’ve mostly hurt the people trapped under his rule. While Assad’s cronies found ways to bypass the restrictions and grow even richer, ordinary Syrians saw their livelihoods disappear.

There’s a longstanding academic debate over whether sanctions actually work. Type “Do sanctions work?” into Google Scholar or Scopus, and you’ll find a dense forest of conflicting research. The empirical evidence shows that sanctions are mostly unsuccessful. Sanctions are attractive to politicians because they project resolve without requiring costly intervention. But in practice, they often fail to produce regime change or even modest reforms.

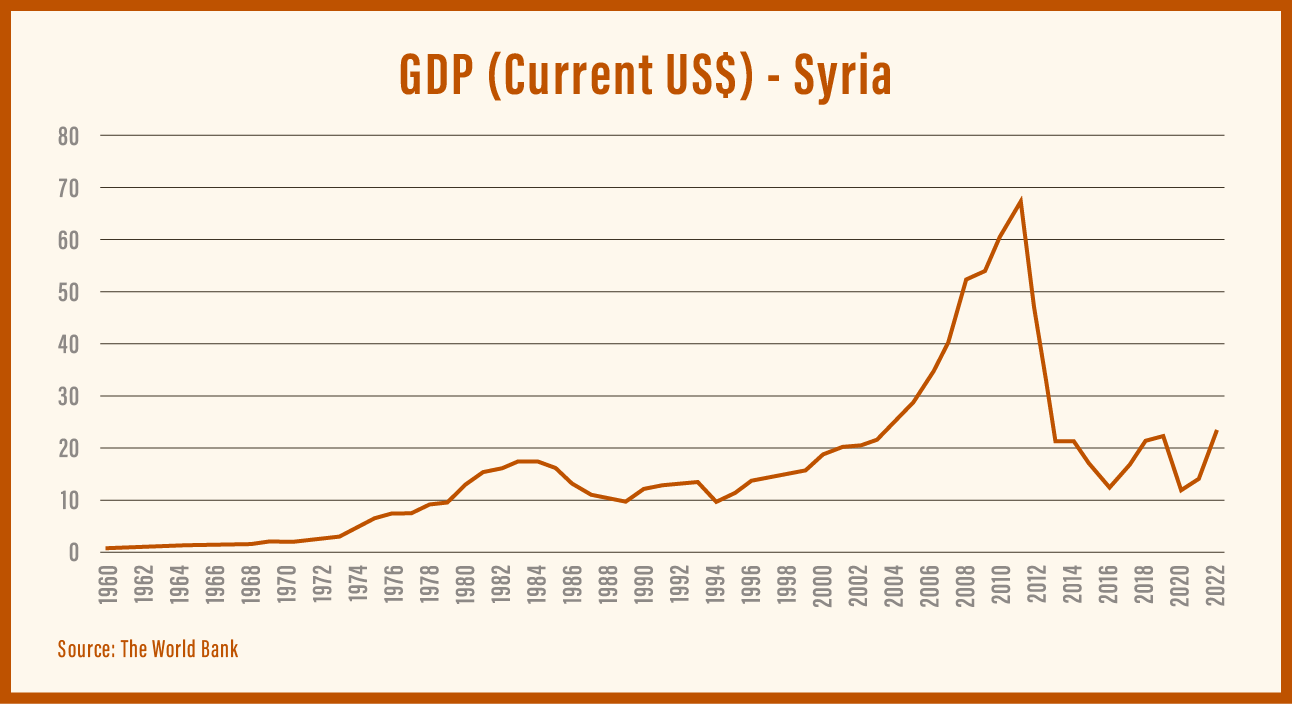

Sanctions on Syria aren’t new. They stretch back to 1979, when the United States designated Syria a state sponsor of terrorism, citing ties to Hezbollah in Lebanon. More were added in 2004 through the Syria Accountability and Lebanese Sovereignty Restoration Act. Yet even under these constraints, Syria’s economy grew—from $9.9 billion in 1979 to $67.5 billion in 2011. While growth was attainable, the distribution of income was sharply skewed, showing the impact of Assad’s nepotistic privatization that aggregated 60% to 80% of Syria’s economy in the hands of Assad and his regime.

What halted that progress wasn’t economic pressure, but war. Then came the Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act, passed in 2019 and implemented in 2020, which ratcheted up sanctions even further. The goal was to deny Assad the resources to wage war. But once again, it was civilians who paid the highest price. Basic goods became scarce. Humanitarian aid dried up. The economy cratered.

Lifting these sanctions, as Trump proposes, may offer a path to recovery. It could enable international aid to flow more freely and encourage foreign investment—two forces essential to rebuilding a functioning state. Investors won’t pour money into a war zone. But if stability improves, capital follows. And when investments create jobs, stakeholders multiply—and so do incentives to maintain peace.

Syria enjoys a comparative advantage in labor-intensive industries, as the average salary amounts to just a few meager dollars per month. This economic reality positions Syria as a potentially lucrative destination for investors. In addition, its diverse terrain—including a vibrant coastline along the Mediterranean, mountains, and the desert in the east—offers numerous tourism opportunities. But investors need more than cheap labor and scenery. They need legal protections, the rule of law, and functioning institutions.

That’s where things get tricky. Syria’s interim president has signaled a desire to align with the West. He has expressed openness to joining the Abraham Accords, expelling foreign militants, and cooperating in the fight against ISIS. These are the right signals—but will they be followed by action?

During Trump’s meeting in Riyadh with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan (via video), and Syrian interim President Al-Sharaa, the U.S. outlined clear expectations. These include Syria assuming responsibility for ISIS detention centers, joining the Abraham Accords, expelling foreign terrorists, respecting human rights, and undertaking constitutional reforms that limit presidential powers and enshrine civil liberties.

Right now, the country’s so-called constitutional declaration concentrates power in the executive and offers few real checks. If it remains symbolic, optimism will remain low. But if it evolves into a true constitution—one that protects rights, guarantees equality before the law, separates powers, and establishes independent institutions—it could mark a new beginning.

The new government faces monumental challenges. Syria’s territory remains divided, with Kurdish-led forces controlling the northeast, and various militias operating in the northwest and south. Foreign fighters remain entrenched. Unifying the country—politically and territorially—must be the top priority.

The government must also rebuild ministries, including a national defense structure capable of restoring sovereignty without falling into authoritarianism. That requires balancing security with rights, unity with diversity, and power with accountability.

If Syria fails to undertake meaningful reform, lifting sanctions could simply empower a new authoritarian regime under the guise of reconstruction. But if done right, it could help usher in a modern, secular, rights-based state.

The road to recovery is long and uncertain. But for the first time in years, a real opportunity exists. The ball is now in the court of the new Syrian state, and its actions will determine how the situation unfolds. Whether Syria becomes a functioning state or slides back into chaos depends not just on the lifting of sanctions—but on what comes next.

Middle East Uncovered is powered by Ideas Beyond Borders. The views expressed in Middle East Uncovered are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Ideas Beyond Borders.