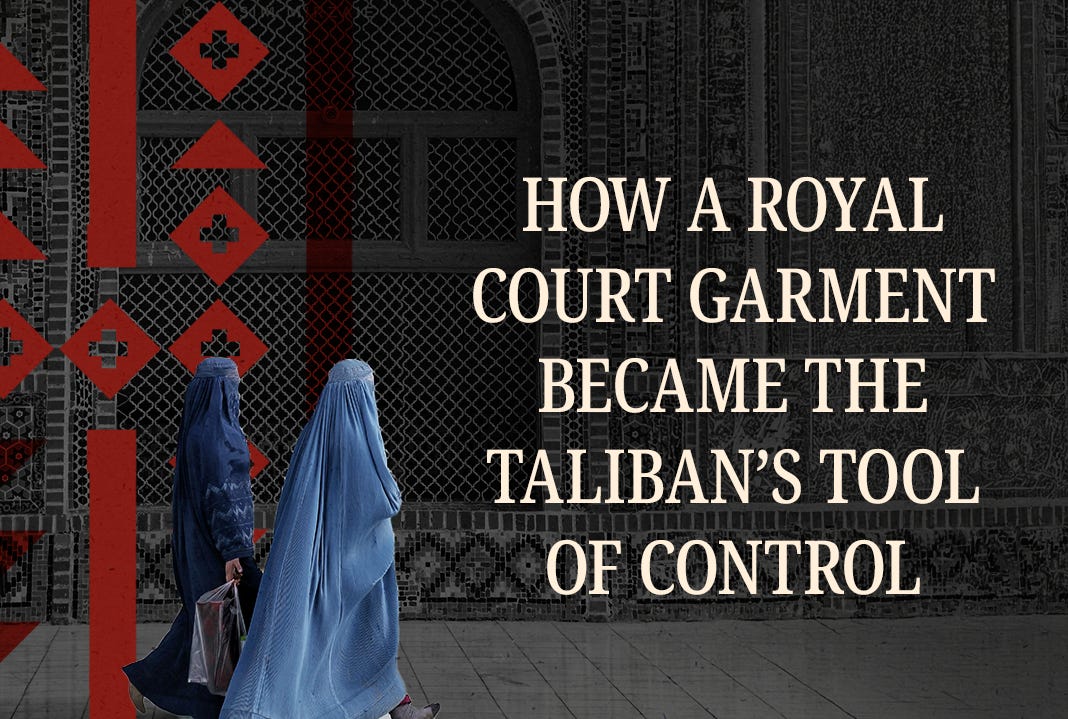

How a Royal Court Garment Became the Taliban’s Tool of Control

What began as a symbol of elite seclusion has become a mechanism for enforcing obedience. The Taliban’s use of the chadari shows how clothing can be weaponized against women’s autonomy.

When Taliban officials in Herat began blocking women from entering hospitals this month for not wearing the blue chadari (or burqa, as it is known in the West), it appeared to be yet another tightening of Taliban rule. But the garment, now used as a gatekeeping tool in healthcare, did not begin in Afghanistan, nor in religion, nor in the customs of ordinary people. Its origins lie in a very different world: the elite royal households of empires.

The story starts long before the Taliban, long before modern Afghanistan was created, and long before Islam.

Across the ancient Mediterranean and Near East, seclusion was synonymous with status. In classical Greece, women of aristocratic households veiled heavily in public; those of lower status did not. In the Achaemenid Persian world, elite women traveled behind curtains in enclosed carriages, unseen by outsiders. Seclusion worked less as a moral prescription and more as a social hierarchy. The more invisible a woman was, the higher her rank.

This logic then spread into the Persian, Timurid, and Mughal courts. From the medieval period to the 1500s, royal and noble women lived behind purdah, literally “curtain” in Persian, enforced through screens, balconies, and palanquins. When elite women appeared outside, they wore a chador cloak and a separate face veil: the rū-band or pīcheh. The system was architectural as much as sartorial. It kept noble women hidden, while ordinary women worked publicly without these restrictions. There was still no burqa as we recognize it.

That changed in the late sixteenth century.

A folio of the Akbarnāma, painted around 1590 in Mughal India, shows three women travelling by boat. Two are enclosed in fully tailored garments: a cap, a long pleated cape, and a screened panel over the eyes. The third woman’s veil is pushed back, revealing her face. Sitting beside them is a servant, unveiled, hair showing. The hierarchy is deliberately on display. This is the first visual evidence of a true mesh burqa form, worn exclusively by elite women. Servants were not allowed to wear it. Ordinary women wore bright clothes, jewelry, patterned fabrics, perhaps a dupatta or light scarf. The full-body veil was not a religious symbol. It was a court uniform of prestige, used by both Hindu and Muslim aristocratic households.

From this Mughal epicentre—Agra, Delhi, Lahore, and Kabul—the garment spread through elite marriage alliances and courtly imitation. Kabul, culturally tied to both the Persian and Mughal worlds, absorbed these styles not through rural tradition but through royal families, administrators, merchants, and Qizilbash households. By the early nineteenth century, the chadari appeared in paintings by James Atkinson and James Rattray: white, pleated, with a mesh screen over the eyes. These images depict Kabul’s urban elite. They do not show farmers’ wives, nor nomads, nor women of the northern valleys. The chadari was still urban and still class-bound.

Around the same time, in Qajar, Iran, elite women wore face-covering veils and horsehair masks, garments related to the Mughal burqa. But in 1936, Reza Shah banned these forms entirely under the Kashf-e hijab decree. The courtly face veil in Iran disappeared. In India and later Pakistan, the burqa experienced no legal abolition, but it declined steadily throughout the twentieth century with urbanization, women’s education, and the spread of lighter head coverings. The full-body veil faded across much of the region.

Afghanistan then decided to take the opposite path and began enforcing it more widely.

By the early nineteenth century, a small number of ordinary urban Afghan women were wearing the chadari, but it remained limited. Rural regions maintained distinct traditions of dress: brightly embroidered shawls in Badakhshan, patterned robes in Bamiyan, light scarves in Kandahar. The chadari was overwhelmingly an urban garment, tied to class and respectability.

That began to shift by the late nineteenth century. As urban life expanded, the chadari became an aspirational marker. Respectable families, not wealthy enough to be elite but close enough to the city’s social institutions, adopted the garment as a sign of modesty and status. By the early twentieth century, it was widespread enough for the state to intervene.

In 1903, King Habibullah banned the white chadari and introduced color rules: khaki for Muslim women, yellow for Hindu women, and slate for others. This system of differentiation has roots across the Islamic world, but its Afghan application shows how central the chadari had become to public space. For the first time, color was used to identify communities of different ethnic and religious groups through clothing—a political decision, not a cultural one.

The twentieth century then reshaped the garment again.

Synthetic fabrics and machine pleating allowed mass production. New regional palettes took hold. Burnt oranges and deep greens become common around Jalalabad. In the Hazara regions, yellow versions appeared. In the northern provinces, white remained popular among older women. Around Kabul, a mid-blue synthetic fabric became fashionable—light enough to manage, sturdy enough to pleat, and inexpensive.

When the Taliban enforced strict dress codes in the 1990s, Kabul’s blue version became the de facto uniform in areas under their control. Western media now codifies it as the defining image of Afghan womanhood. What began in palaces became a national symbol.

It is against this backdrop that the Herat hospital restrictions land. A garment engineered centuries ago to protect elite women from the public gaze is now being used to deny ordinary women medical care. Afghanistan already suffers from one of the world’s highest maternal mortality rates. Restrictions on women’s movement, shortages of female medical staff, and the collapse of parts of the healthcare system make the problem worse.

For the Taliban, the chadari today is not just clothing; it is a governing tool. It functions as a visible measure of obedience and a way to compress all Afghan women into a single silhouette that can be policed at a glance. A woman who appears without it is read not as improperly dressed, but as defiant, a threat to the moral and political order the Taliban claim to embody. In this logic, enforcing the burqa at hospital gates becomes a test of submission. The message is simple: healthcare is conditional on conformity.

Afghan women understand this politicization clearly. Many describe the chadari not as modesty but as necessary for survival: you disappear inside it so you can move through Taliban-controlled spaces without being noticed. Younger women who never grew up wearing it now experience it as a uniform of erasure, the garment the Taliban use to signal that public life belongs only to men. And so they push back in small but deliberate ways: removing the chadari once past checkpoints, wearing thinner or shorter versions that technically pass inspection, using masks and long coats as alternatives, and sharing information on lenient clinics and sympathetic guards. These micro-acts do not overthrow the rule, but they carve out slivers of autonomy within it.

And there is one more layer to this story—the way the garment has come to define Afghanistan in the global imagination. No other Muslim-majority country uses the Afghan chadari in this form: the stitched cap, the pleated canopy, the mesh screen. It is visually distinct, instantly recognizable, and therefore easily generalized. Colonial photography fixed that image early. Throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Western travelers and soldiers depicted Afghanistan as a tribal frontier, a place outside time, its women hidden behind unfamiliar veils. Those images circulated widely, and postcards, travelogues, geopolitical reportage, and the chadari became shorthand for a society described as backward, unknowable, and unchanging. That impression stuck.

A garment born in royal courts has become a tool for restricting movement, visibility, and even access to life-saving care. But its long history shows that meanings shift, and Afghan women—through small acts of noncompliance—are already imagining a future where the chadari no longer defines their place in the world.

Middle East Uncovered is powered by Ideas Beyond Borders. The views expressed in Middle East Uncovered are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Ideas Beyond Borders.

The resilience of Afghan women is the promise that the future need not be draped in the fabric of the past.

May their unwavering spirit soon secure a world where dignity is measured not by what covers them, but by the freedom and respect they can openly claim.