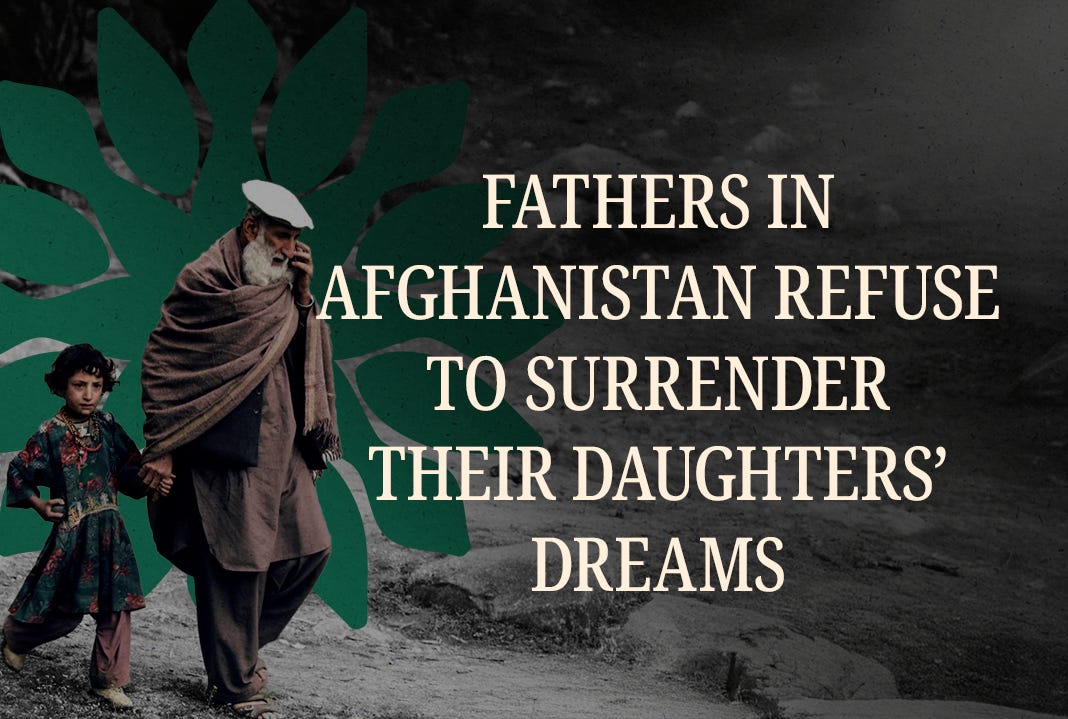

Fathers in Afghanistan Refuse to Surrender Their Daughters’ Dreams

Under Taliban rule, Afghan fathers struggle to stay hopeful for daughters they can no longer protect, and for a future that feels increasingly out of reach.

Middle East Uncovered uses pseudonyms to protect our sources in Afghanistan.

The rush of joy when Sayed held his baby daughter for the first time was fleeting. At 20, he was a first-time father, anxious to give the tiny, precious human in his arms the best chances in life. But looking down at his little girl, he felt her happiness had an inevitable expiration date.

“After the initial joy, I felt hopeless,” he said. “In the future, she cannot pursue her studies like girls in other countries, cannot make a good life for herself.”

His concerns echo those of countless fathers across Afghanistan who feel powerless to intervene as their daughters, wives, and sisters watch their dreams dissolve. Women who once led full, productive lives are now stuck at home, hope ebbing under a regime that grows increasingly hardline.

As the crisis in women’s rights deepens, the impacts are sending shockwaves through every aspect of Afghan society—crippling the economy, straining healthcare, and eroding social stability. The UN Women’s 2024 Afghanistan Gender Index shows how the systematic exclusion of women is reversing two decades of progress and plunging the country deeper into poverty and instability.

“Three years ago, the world was watching a takeover that was livestreaming horror after horror,” said Alison Davidian, UN Women’s country representative in Afghanistan. Speaking last August during the launch of the report, she said: “While the world’s attention may have turned elsewhere, the horrors have not stopped for Afghan women and girls, but nor has their conviction to stand against the oppression.”

With half the country held hostage, families are struggling to adapt. Women and girls grieve the loss of the lives they planned amid an escalating mental health crisis that has seen a rise in depression and suicide attempts. Meanwhile, men are feeling the strain as households, many reduced to a single income, navigate financial hardships amid an economic crisis.

For fathers like Sayed, everyday concerns are compounded by fears for the future. His daughter is just eight months old, but he worries about the society she will grow up in. “We are afraid of the country lagging behind the rest of the world,” he said. “We want Afghanistan to advance, for our sisters to be able to study and work.”

A university graduate, he is barely making a living selling knick-knacks from a stall on the street. He worries that the Taliban is here to stay. “I am extremely concerned about my family and the overall situation. My country is plunging into darkness,” he told Middle East Uncovered during a remote interview last week.

Since seizing power in August 2021, the Taliban has systematically dismantled women’s rights, shutting them out of secondary school, university, and most fields of employment. Activities that once felt normal—weekend picnics at the park, visiting local sports clubs, and walking freely down the street—are now off-limits to women, and strict rules on clothing mean many are afraid to leave the house.

Education is being transformed into a mechanism for indoctrination as the Taliban seeks to mold a new generation in its image. Qualified teachers, many of them women, have been forced out, replaced in some cases by regime loyalists, many of whom lack proper teaching qualifications.

School textbooks have been rewritten and curricula revised to reinforce the Taliban’s agenda. Art and sports are out, while lessons in Islam have increased.

A growing sense of paralysis grips many families as these changes take hold.

Haady’s wife, Maryam, lost her job in the early days of the new regime when thousands of female teachers were let go. At first, the couple ran a secret school at home, but their savings ran out after six months.

No longer able to help Afghan girls and boys build a bright future, Maryam has lost her glow. She moves through the house like a ghost, Haady said. “She is suffering all the time. You can see her pain.”

Their daughters, aged 18 and 16, still dream of working in medicine and education. They ask him constantly when schools and universities will reopen. “They say we want to learn, Father, take us away from here. To be honest, I have nothing to say to them; it’s out of my control,” he said.

The systematic exclusion of women from public life is having knock-on effects at home as the Taliban’s campaign of erasure expands. With female faces no longer visible on television, in public office, or at official events, women’s status is waning.

UN Women reported a 60 percent drop in the number of women who feel they can influence decisions, even within their own households. Ninety-eight percent of women feel they have limited or no influence over decisions in their communities.

While Haady’s daughters can no longer learn, Najib clings to the last days of his daughters’ education. At eight and ten, it won’t be long before the eldest is barred from going into school.

Najib’s own schooling was neglected, so educating his children is a priority. “If we want freedom and peace for the future of the country, we need to educate our women,” he said.

Returning from work at a curtain shop every evening, the mood at home feels tense. “Since the Taliban came to power, the atmosphere has changed dramatically. There is this sense of hopelessness, and we are no exception,” Najib added.

The economic uncertainty that followed the Taliban takeover forced men as well as women from their jobs. Unemployment spiralled and prices rose, deepening a financial crisis multiplied by decades of conflict.

Despite signs of recovery, with modest GDP growth of 2.7 percent in 2023-2024, poverty remains rampant, with 40 percent of the population facing acute food insecurity and over half of Afghans reliant on dwindling humanitarian aid.

Khalid works in a grocery store and struggles to sustain his family on around $75 a month. Like many Afghans, he believes that more children bring better fortune to sustain their parents in old age. But Khalid’s eldest are girls and are unable to support the family after being barred from school in the final stages of their studies. “It’s extremely hard. I was counting on my girls. This is the concern of hundreds and thousands of fathers,” Khalid said. “My boys are teenagers, and I am aging. This is not sustainable for us.”

Khalid lived through the first Taliban era from 1996 to 2001 and views their return with disbelief. Over a 20-year period, life in Afghanistan changed dramatically as women entered public life, holding political office and launching businesses.

Education was overhauled, and attitudes started to shift. Between 2001 and 2021, enrollment of girls in primary school rose to over 80 percent, and literacy among women increased from 17 percent to almost 30 percent.

In July 2021, 27 percent of Afghan MPs were women, and 20 percent of civil servants were female, while the number of female-owned businesses increased.

“We were more educated, and there was more money. We could never anticipate the return of the Taliban,” Khalid said.

The speed of the group’s power grab took everyone by surprise. When the militants swept into Kabul on August 15, 2021, tens of thousands fled, leading to harrowing scenes outside the airport as people clung to the wings of planes, desperate to escape.

As they moved to establish their hold on the country, Taliban promises to respect women’s rights evaporated. Schools were swiftly shut down, and female employees were sent home.

A constant stream of fresh directives intensified the pressure. Last August, a new Vice and Virtue law enshrined the Taliban’s attempt to muzzle women by prohibiting them from speaking, singing, or praying in public.

NGOs, meanwhile, have been instructed to remove the word “woman” from their organizational names, and dress codes now mandate the burkha for women in Kandahar, the Taliban’s stronghold.

Efforts have also been made to prohibit women from using smartphones. At the same time, a recent internet shutdown threatened the last avenue of freedom for women and girls pursuing education and employment online.

As this gender apartheid regime reaches new heights, Afghan society is paying a steep price. Haadiya, 23, sees the impact in the hospital where she works as a midwife, one of the few avenues still open to women. Even this will soon be impossible with the ban on higher education leaving a massive gap in healthcare for women, who are forbidden from seeing a male doctor under Taliban rules.

Haadiya’s 22-year-old sister was not allowed to complete her medical training and is now out of work. Instead, their 15-year-old brother has quit school to sell goods in the street.

“Thousands of girls like myself who work to facilitate life for their families are out of the picture,” Haadiya said. “Some fathers have lost their jobs and are begging on the streets. The Taliban are making things harder by the day.”

For women and girls forced to stay at home, life is increasingly hard to bear. Ahmed’s 14-year-old daughter tries to contain her feelings as she watches her younger brother do his homework. “I try to motivate her, give her hope, tell her I will do my best, but there is only so much I can do,” he said. “My son doesn’t want to study in front of her, so he sometimes skips work or goes to another room.”

Ahmed studied up to 10th grade and assigns them both homework, but it’s not enough to provide a proper education. “I can only do so much—we cannot replace the role of teachers,” he said.

Across Afghanistan, a generation of girls and boys is watching their dreams slip away. As opportunities narrow with each new decree, fathers like Haady, Khalid, Sayed, Ahmed, and Najib feel powerless to intervene. Yet many still try, teaching lessons at home, reading to their daughters in secret, and finding small, safe ways to keep their girls’ minds alive. Around them, life is changing, but their beliefs remain the same as they long for a future in which girls can learn, work, and live without fear.

For now, that feels far-fetched, and hope is suspended as they wait for changes that may never come. “The future is completely dark,” Haady said. “Our girls will not be good mothers if they themselves know nothing.” Like many Afghans, he feels abandoned by the international community as their plight slips down the global news agenda and the Taliban tighten their grip. “We are so eager to raise our voices and stand against this regime, but we need to be sure the world is listening,” Haady said.

Middle East Uncovered is powered by Ideas Beyond Borders. The views expressed in Middle East Uncovered are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Ideas Beyond Borders.