Christmas In Damascus

The season’s celebrations offered an honest view of a city navigating relief, restraint, and unresolved questions about the future.

This year, I finally overcame my fears and decided to visit Damascus and spend Christmas there. I stayed in a traditional Arab house hotel in Bab Touma, in the heart of the Old City, where the Christian presence remains strong and architectural memory endures in stone alleys and inner courtyards. The place offers a condensed view of Damascus with all its history, diversity, and stubborn life force that persists despite everything the city and its people have endured.

Although electricity was intermittent, Christmas decorations appeared throughout Bab Sharqi and Bab Touma, Al-Qaimariyya, Qassaa, Shaalan, and Malki. Trees lined cafés and storefronts, and locals joked that Muslims were as eager as Christians to photograph them. It was an ordinary scene in a community long accustomed to living its diversity.

Security was visibly present. Public security forces guarded religious sites, gatherings, and celebrations without heavy or demonstrative displays, and their presence was generally reassuring. Markets were crowded, but spending remained limited, reflecting high prices and weak purchasing power.

This year’s Christmas carried the aftertaste of political rupture. The holiday’s joy was infused with optimism for a new year, the first without sanctions following the fall of Assad and the lifting of the Caesar Act on the first anniversary of the regime’s collapse. Street banners openly commemorated the moment: “The black era is over.” “How beautiful you are, my country, without Assad and without Ba’ath.” “Those who killed us have fallen.”

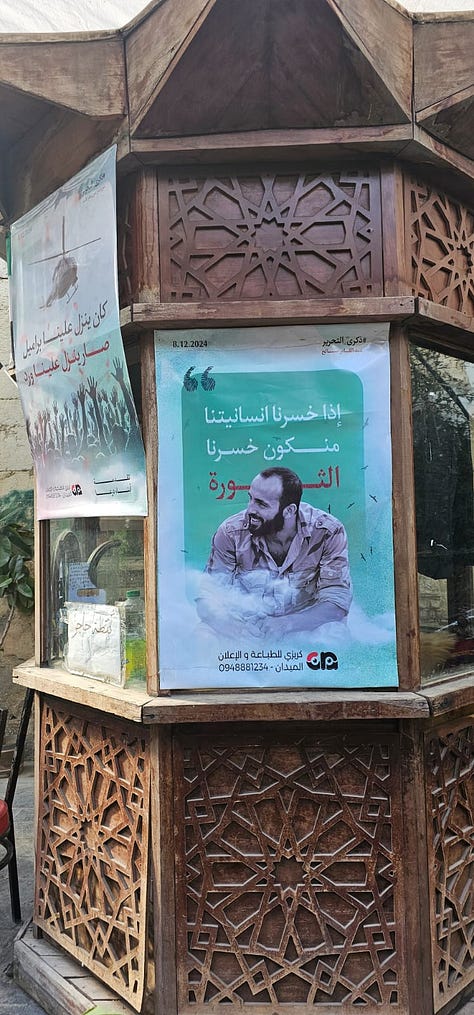

Another phrase appeared repeatedly, attributed to Abdul Qader Saleh, one of the founders of the Free Syrian Army, killed by Assad’s forces in rural Aleppo in 2013: “If we lose our humanity, we lose the revolution.”

Daily life unfolded without pretense. Alcohol was freely sold and served, especially in Bab Sharqi and Bab Touma, and social life followed local customs.

At the same time, there was a noticeable degree of self-censorship around clothing, public drinking, and loud celebration. I visited places once known for their rowdiness, now markedly calmer. There are no formal bans on celebration, but individual incidents over the past year, attributed to people linked to security forces, appear to have encouraged restraint.

Over two days, I spoke with Syrian Christians and encountered two sharply opposed outlooks. One was cautiously optimistic, believing the new authorities navigated a potentially disastrous year with relative wisdom, and viewing what occurred on the coast and in Suwayda as individual abuses for which accountability would follow. The other was deeply uneasy, fearing the Islamization of public space and haunted by what befell Alawites on the coast and Druze in Suwayda.

What stood out was the extent to which the first camp places genuine faith in the new state’s narrative. They believe the violence was neither systematic nor sectarian, that earlier religious rigidity and factional logic have been abandoned, and that the country is moving toward institutions rather than militias. President Ahmed Al Sharaa, once the emir of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, a widely designated terrorist organization with Salafi-Jihadist roots, is still seen by some not as a transformed leader but as Abu Mohammad al-Jolani under a new name. They are convinced he remains a radical Islamist, merely adopting the language of pragmatism. Others are more pragmatic themselves. They have chosen to work, build, and move forward, viewing the new authority as a partner in liberation from a regime that crushed them for six decades.

Politics was everywhere. This was a Christmas saturated with political conversation. Discussions about the future were constant. Civil society is stirring, and development initiatives are widely seen as urgent. Criticism and the open expression of opinion are new and oddly exhilarating phenomena, heard in bars, restaurants, and alleyways alike. Such openness would have been unimaginable under the fallen regime.

Tourism is cautiously returning. Jordanians like myself, other Arabs, and Europeans were visible, alongside many Syrians from Europe and the United States. Gulf visitors were fewer than expected. People were eager to welcome tourists, offering help in the distinctly Damascene manner, with a musical cadence familiar from Syrian television dramas long beloved across the Arab world.

Alongside the holidays, infrastructure repairs were underway in the Old City. A garbage dump in front of historic Bab Sharqi is being relocated to an uninhabited area, with plans to turn the site into a large parking facility to serve a district frequently congested by traffic. I also heard discussions about banning cars from these streets altogether, prioritizing pedestrians, and improving the visitor experience. It was genuinely uplifting to see modern garbage trucks, municipal vehicles, police, and security cars, a sharp contrast to the fallen regime’s reliance on battered, outdated fleets, often Russian or Iranian-made.

Damascus this Christmas did not offer clarity or closure, but something more honest: a city testing what is now possible, and what is not. Hope and suspicion coexist in the daily calculations of people who have learned the cost of being wrong. Politics has moved from the shadows into ordinary conversation, and with it has come both relief and unease. Whether the new order becomes a functioning state or hardens into another form of authoritarianism has yet to be seen. What is clear is that Syrians are once again speaking openly, observing carefully, and reserving judgment—a position arrived at less by naive optimism than by the memory of all they have survived thus far.

Middle East Uncovered is powered by Ideas Beyond Borders. The views expressed in Middle East Uncovered are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Ideas Beyond Borders.

Every picture tells a story don't it!

How amusingly dissonant to see conical red xmas hats alongside traditional Arab decorations