Bamyan’s Slopes Held a Generation’s Dreams. Then the Taliban Returned.

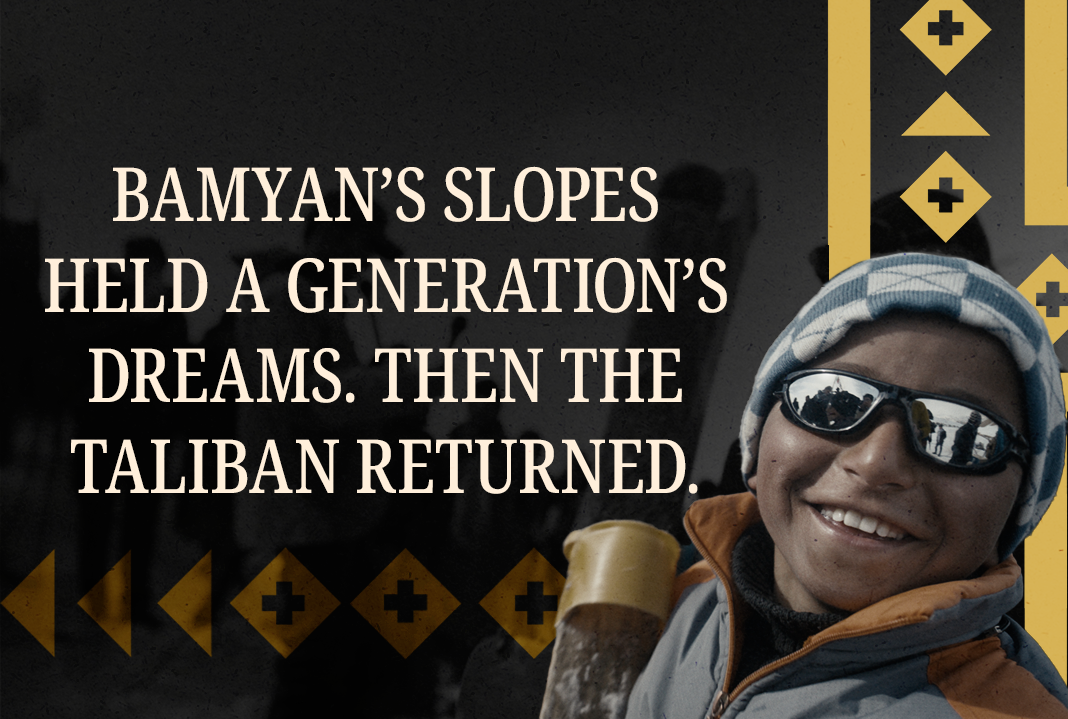

"Champions of the Golden Valley" documents the joy, grit, and ingenuity of Afghanistan’s young skiers. The film preserves the vibrancy and potential of a moment that now feels impossibly distant.

The auditorium at The Cooper Union in New York City was nearly filled to capacity when Champions of the Golden Valley screened last Friday—speaking not only to the film’s growing reputation, but to the hunger for stories that remind us of our shared humanity in increasingly polarized times. Yet the mood that evening was complicated. With news still fresh of the attack in Washington by an Afghan national and the renewed crackdown on Afghan immigration, the air was thick with hope and heaviness. Into this moment arrived a documentary that powerfully expands our understanding of what Afghanistan is, and who Afghans are.

Director Ben Sturgulewski began filming in Bamyan, Afghanistan, before the Taliban's 2021 takeover. What was intended to be a portrait of an emerging ski culture in a remote mountain community soon became something far more layered and devastating. The young skiers we meet—optimistic, competitive, and full of life—become refugees before our eyes. Their aspirations are cut short as they’re forced into exile.

One skier’s words hung in the theater long after they were spoken: “I never wanted to be a refugee.”

Another offered a line from a bare apartment in Berlin that encapsulates the film’s emotional center: “The power and love of the homeland keep pulling you.”

The documentary becomes, simultaneously, a breathtaking time capsule and a devastating prophecy. We witness joy that we now know will be stolen, and we feel the weight of that impending loss in every frame.

If the film has a throughline, it is tenacity. Bamyan’s residents build their own skis from wooden planks. They fashion a makeshift ski lift. They train by trudging uphill through deep snow—sometimes carrying animals—never complaining and never expecting ease. There’s a contagious determination in their efforts, and that energy rippled through the theater, a reminder of the unbridled joy hard work begets, a joy many in the West have long forgotten.

There is humor and vibrancy, too. Hussein Ali, in a radiant purple ski suit and a flair that makes him unmissable, competes with both style and sass. Due to a historic rivalry, he and the film’s main protagonist, Alishah Farhang, should be enemies, but the slopes tell a different story. Skiing becomes a great unifier—an arena where sport bridges cultural and social divides, creating unexpected moments of peace, laughter, and camaraderie. Their rivalry eventually evolves into a genuine friendship. It’s this unlikely bond with Farhang, the skier whose Olympic dreams anchor the narrative, that gives the film its emotional shape.

And then there is “The Boss,” a young boy who crafts skis for his friends with the seriousness of a seasoned engineer—an image of possibility that feels, today, almost unbearably tender, but elicited an approving chuckle from the crowd nonetheless.

One of the film’s eeriest and most prophetic necessities is the blurring of women’s faces. Village women were not allowed to be shown on film, and their obscured presence now reads as foreshadowing the literal erasure that the Taliban would later impose on Afghan women and girls. That haunting visual became even more significant after the Taliban takeover, when the director and producers had to help the women and girls from the ski team flee the country precisely because their participation made them targets. The team’s coach, too, became a target for the same reason: he had trained a female team.

The emergence of a girls’ ski team and the shock it generated among some villagers stands out despite their faces being obscured. The film grants them a place in the narrative long before the world knew just how soon their already limited freedoms would be taken from them.

Farhang’s father, a mullah, becomes one of the film’s most surprising figures—not because he challenges his son’s pursuits, but because he embodies a gentle, inclusive faith rarely depicted in Western media. “We’ve all been created by God,” he says, offering a counter-image to the caricatured Islamic leaders that dominate Western imagination.

This is one of the film’s subtle triumphs: it forces viewers to confront how thin and reductive our narratives about Afghanistan have been. The complexity, humor, contradictions, and expansive humanity of the Bamyan community push back against decades of oversimplification.

When the Taliban seize control, and Farhang is forced to relocate to Berlin, the documentary abruptly shifts to black and white. Gone are the saturated mountain landscapes, the colorful patchwork of ski gear, and the cheering crowds. In their place: a stark palette that mirrors displacement, grief, and the claustrophobia of trying to rebuild identity in a foreign land.

This stylistic turn is more than aesthetic, and tears open an emotional rupture. Watching it from the vantage point of 2025 as Afghanistan continues to reel under repressive rule, the contrast was difficult to watch.

The film gestures toward Afghanistan’s long pattern of interrupted futures. From the 2001 bombing of the Bamyan Buddhas to the terror attacks of 9/11 occurring just six months later, history documents a series of blows absorbed by people who keep striving despite them. Afghanistan, situated at the crossroads of empires, trade routes, and conquests, carries a significance that is both geographical and existential. In the film, the coach described Afghanistan as a “war country,” a phrase that captures the normalcy of conflict in a place where people learn to get “used to it” and simply “go on.”

What the film makes clear is that the country’s people have always perservered, even when the world’s gaze moved elsewhere.

Watching Champions of the Golden Valley today feels like inhabiting two timelines:

the bright, unrealized future the skiers were reaching for, and

the somber present in which that future has been violently cut off.

The film offers a portrait of an alternate Afghanistan—one where the ski challenge continued, where Farhang and his peers built something lasting, and where the world knew Afghanistan not only for its wars but for its athletes, its mountains, its ingenuity, and the laughter of its people. The film becomes an inadvertent archive, capturing gestures, landscapes, and moments of levity that the Taliban’s return has made precarious and difficult to imagine reclaiming.

That universe feels painfully close. And irrevocably out of reach.

In tracing the rise of the Afghan Ski Challenge, the film also redefines what it means to be a champion—not merely someone who wins races, but someone who insists on building community in one of the world’s most unforgiving countries, who uplifts remote villages, bridges rival groups, and believes that sport can cultivate a more fulfilling society. This vision endures even in exile: Farhang, now living abroad, teaches his young children to ski on new mountains, a resonant full-circle gesture that keeps the dream alive thousands of miles away from home.

By the time the credits rolled at The Cooper Union, many, including myself, were in tears. A wish lingered in the room that one day, the Taliban will fall, and the Afghan Ski Challenge will return to the mountains of Bamyan.

Until then, Champions of the Golden Valley is an enduring historical record—both of what was and what could still be. A reminder that even in the world’s most troubled places, people dream of nothing more radical or more human than living a good life.

Middle East Uncovered is powered by Ideas Beyond Borders. The views expressed in Middle East Uncovered are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Ideas Beyond Borders.